“Officers who deal with human trauma might not recognize its toll till too late.”

KEY POINTS

- Repeated exposure to trauma can weaken the ability to cope, resulting in cumulative PTSD (CPTSD).

- Since it’s not linked to a specific incident, CPTSD can go undiagnosed.

- Educating police officers about CPTSD can inspire preventative treatment that benefits the whole organization.

In the Boston Globe recently, Nicholas DiRobbio described a disabling condition that forced him out of his job as a cop. One day, something just seemed to come over him. Common noises like kids shouting jarred him. He grew scared to leave his house. Some days he sat in his cruiser and screamed. He didn’t recognize himself.

“As a cop, you struggle with your identity,” he told the Globe. “You can’t reform, and you’re broken—you’re not that person and that hero you used to be.” Finally, he quit the force and sought counseling. He knew something was wrong, but he didn’t know what.

DiRobbio learned that he suffered from cumulative post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD), or the sum reaction to a build-up of trauma over time. It’s like piling one too many bricks on a scaffold that finally collapses.

The Effects of Cumulative Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD)

“I never anticipated that it feels physical,” he said. “It feels like a weight. You get pressure on the chest area, you feel this heavy burden like a pain, and you feel physically uncomfortable in your own body… I was shaking a lot, uncontrollably… Someone who is a police officer and faced all kinds of stuff, I’m not afraid, but my body wouldn’t physically let me leave the house.”

He describes his experience in Invisible Wounds, insisting it’s not a weakness of character as it’s often portrayed but a process beyond one’s control. Dr. Michelle Beshears, in the Criminal Justice Department at American Military University, agrees. “Cumulative PTSD can be even more dangerous than PTSD caused from a single traumatic event,” she states, “largely because cumulative PTSD is more likely to go unnoticed and untreated. If untreated, officers can become a danger to themselves and others.”

We hear a lot about PTSD but not much about this more nebulous condition. Yet, those on active duty who routinely deal with human trauma are vulnerable to it. Law enforcement is one of the occupations at greatest risk, given how much they’re exposed to conflict, trauma, and death.

“I went to 30 incidents of dead people,” DiRobbio recalled. “I remember every single one of them…. There [are] sights and smells and people crying; that sticks with you.”

Cerel et al. (2018) examined the results from 800 officers who’d completed a survey about their exposure to suicide incidents. Almost all participants (95 percent) had responded to at least one such scene, with an average of 31 over a career. One in five reported a scene that had triggered nightmares, and close to half reported seeing things that had stayed with them. The researchers found a significant association between frequent exposure to suicide and behavioral health consequences, mostly depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders—all signals of potential CPTSD.

Supporting First Responders With CPTSD

This mental health injury appears to be a growing issue for first responders. Valazquez and Herandez (2019) reviewed research on police mental health. “Working as a first responder,” they write, “has been identified as one of the few occupations where individuals are repeatedly placed in high stress and high-risk situations.” Typical coping strategies show a failure within organizations to recognize a developing issue like CPTSD. One of the most persistent barriers to seeking help is the stigma attached.

“It is evident that officers unknowingly advocate negative attitudes about seeking mental health support based on the organizational stigma. Organizational stigma manifests in the way the agency prioritizes officer wellness and provides supportive services.” They argue that for the greater good, organizations must address the stigma directly, diminish its impact, and encourage the use of services.

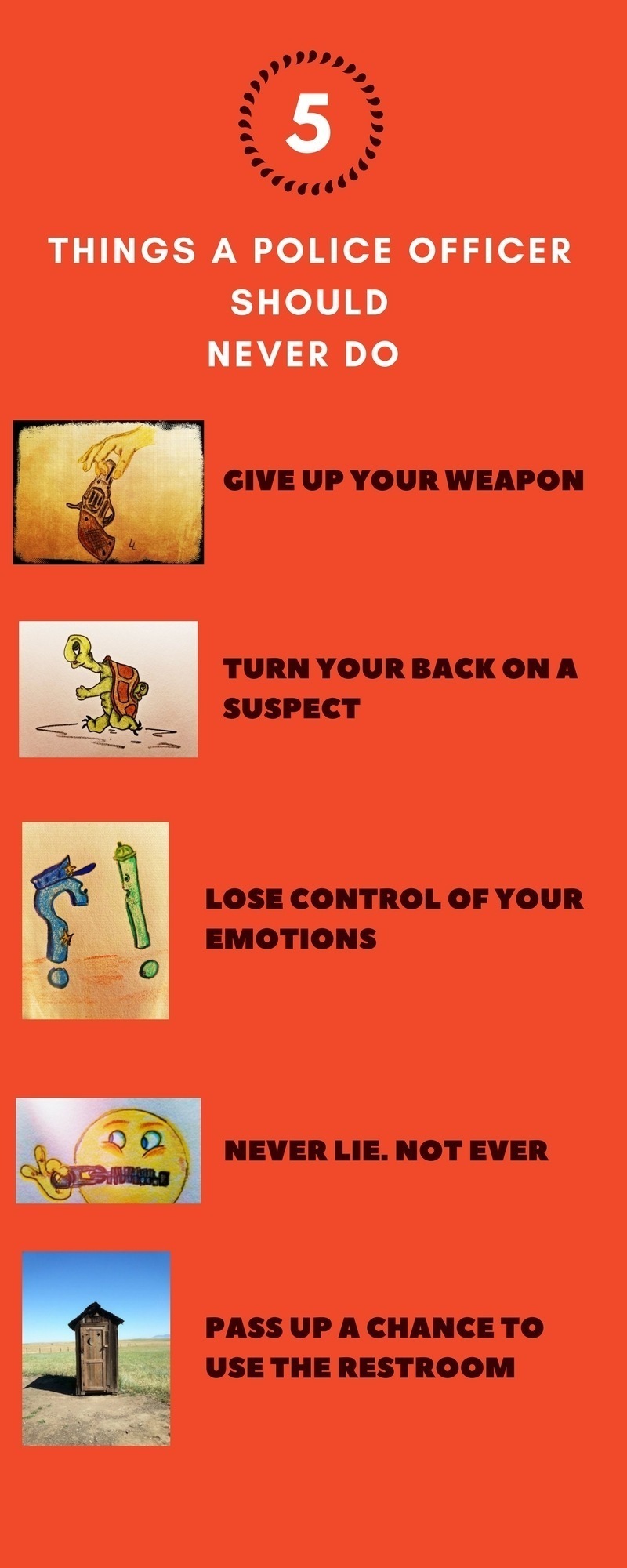

Among the types of experiences that can negatively affect cops are officer-involved shootings, vehicle pursuits, volatile domestic situations, and witnessing the aftermath of rapes, accidents, suicides, and homicides. Symptoms of CPTSD include intrusive thoughts, sleep or eating disorders, adverse mood shifts, withdrawal from friends and family, agitation, physical deterioration, and disorientation.

However, few departments have effective support in place. It’s no secret that the police culture has traditionally dodged the topic of mental health, an approach that has only added to the rise in depression, CPTSD, and suicidalthoughts among officers. They feel guilty, embarrassed, and ashamed about asking. They think their peers will now view them differently. So, instead of expressing their feelings to relieve the pressure, they withdraw. Although some departments now include critical incident debriefing for this purpose, many do not.

Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) is a peer-support process that aims to erase stigma and encourage seeking help. Watson and Andrews (2018) found that in military populations, this instrument has shown beneficial effects. Studies with TRiM in police departments in the UK are ongoing, but early reports indicate a positive reception.

Ignoring mental health problems in cops won’t erase them. Education, training, and support are needed to ensure the welfare of those who keep us safe.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

References

Beshears, M. (2017, April 3). Police officers face cumulative PTSD. Police 1.https://www.police1.com/health-wellness/articles/police-officers-face-c…

Carlson-Johnson, O., Grant, H., & Lavery, C. (2020). Caring for the guardians—Exploring needed directions and best Practices for police resilience practice and research. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01874

Cerel, J., Jones, B., Brown, M., Weisenhorn, D. A., & Patel, K. (2018). Suicide exposure in law enforcement officers. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior.doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12516

Velazquez, E., & Hernandez, M. (2019). Effects of police officer exposure to traumatic experiences and recognizing the stigma associated with police officer mental health: A state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal,42(4), 711-724.

Watson, L., & Andrews, L. (2018). The effect of a Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) program on stigma and barriers to help-seeking in the police. International Journal of Stress Management,25(4), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000071

Velazquez, E., & Hernandez, M. (2019). Effects of police officer exposure to traumatic experiences and recognizing the stigma associated with police officer mental health: A state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal, 42(4), 711-724.

Watson, L., & Andrews, L. (2018). The effect of a Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) program on stigma and barriers to help-seeking in the police. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(4), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000071

______________________________________________________________________________________________

This article originally appeared in the October 18, 2021 of “Psychology Today.” It is published here with the permission of the author, Katherine Ramsland Ph.D.

Cover photo by Katherine Ramsland.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200 crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,000 articles and 68 books, including How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and The Mind of a Murderer, she spent five years working with Dennis Rader on his autobiography, Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer. Dr. Ramsland currently pens the “Shadow-boxing” blog at Psychology Today and teaches seminars to law enforcement.

Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200 crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,000 articles and 68 books, including How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and The Mind of a Murderer, she spent five years working with Dennis Rader on his autobiography, Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer. Dr. Ramsland currently pens the “Shadow-boxing” blog at Psychology Today and teaches seminars to law enforcement.

Officer Bradley Fox, 34

Officer Bradley Fox, 34

Spots are still available to the 2018 Writers’ Police Academy. Yes, registration is still open and, we have lots more surprises on the way. This is an event you’ll remember for a lifetime so please hurry while slots are available! Oh, be sure to refer a friend and have them sign up as well. You’ll soon see why that could be a very important step.

Spots are still available to the 2018 Writers’ Police Academy. Yes, registration is still open and, we have lots more surprises on the way. This is an event you’ll remember for a lifetime so please hurry while slots are available! Oh, be sure to refer a friend and have them sign up as well. You’ll soon see why that could be a very important step.