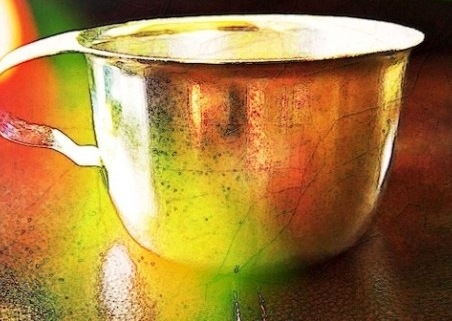

An old tin cup sits on a shelf in my office. People who see it rarely ask about it, with most not giving it so much as a second glance.

The cup, while scratched and slightly dented, still has a bit of shine left on its surface, Those thin etched lines resemble an intricately-drawn roadmap. And, if one knows the history of the cup, well, each line is indeed a well-traveled path, and each line has a story to tell. While I don’t know the details of all of the stories held by my old tin cup, I know a few.

When the cup was first manufactured, World War II had recently ended as had the manufacturing of cordite. Schools in Virginia had not yet been fully integrated and Arthur Ashe’s father was working as a Special Policeman for Richmond, Virginia’s recreation department. Arthur Ashe was the only African American man to ever to win the singles title at Wimbledon, the US Open, and the Australian Open.

As tin cups made their way from factories to their final destinations, the Virginia State Penitentiary complex, built in 1800 at Belvidere and Spring Street, in Richmond, was in full swing. It was a horrid place that was so bad the ACLU once labeled it the “most shameful prison in America.” But it didn’t start out that way.

The idea to build the Virginia State Penitentiary was brought to the table by Thomas Jefferson.

In 1785, Jefferson served in Paris as ambassador. It was then and there when he noticed a different type of incarceration, one that was an experiment of the effect of labor by inmates in solitary confinement.

Jefferson believed that the object of punishment should be discipline, repentance and reform. Not as vengeance. So, when he returned from Paris he proposed his “labor in confinement” for prisoners. His idea was to have prisoners work on public works projects during the day then spend their non-work hours in small solitary confinement cells so they could reflect on their crimes.

It was 10 years later when Virginia lawmakers moved forward on Jefferson’s plan. Construction began on the Virginia State Penitentiary, soon to be nicknamed “Spring Street,” a moniker used by both inmates and staff. The name Spring Street quickly became associated with darkness and torture and pain … and the electric chair.

Prisoners at Spring Street drank from tin cups, much like the one in my office.

The Virginia State Penitentiary was designed by architect Benjamin Latrobe, who later designed the U.S. Capitol.

The cell doors at the Spring Street prison had no windows, which meant that officers had to physically open them to check on the inmates inside. The prison was unheated, and believe me, it gets cold in Virginia during the winter months.To keep warm, prisoners wrapped themselves with thin German-made wool blankets. Each prisoner was give one blanket, their only protection against the freezing blasts of air that blew in through the barred windows.

The prison was not equipped with a sewage system; therefore, prisoners were forced to collect waste in buckets and then empty them down a trough that flowed into a nearby pond. Summertime in Richmond, Va. can be extremely hot with humidity so thick that flies nearly swim in mid air. It was after 100 years had passed by that officials decided to improve the sewage situation.

Tin cups remained in use throughout, during executions, riots, the incarceration of both notorious and noteworthy inmates, such as former U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr, serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, and the evil Briley brothers, a duo whose vicious and vile crimes I’ve written and about and detailed here on this blog.

At the close of the the Civil War, the entire population of the Spring Street prison escaped following the Richmond evacuation fire.

The tin cups, though, remained at the prison, waiting for the return of the prisoners.

Hundreds upon hundreds of tin cups where in use just a half-mile away.

Virginia began executions by electric chair at the Spring Street penitentiary in 1908. The last hanging was in 1909. Executions took place barely a half mile from the center of Virginia Commonwealth University’s campus, where in later years (much later) my wife Denene was hard at work earning her PhD in pathology.

A few blocks further down the way was the location of the state lab where I delivered crime scene evidence for examination and testing. The state morgue was also there. It was the place where I observed numerous autopsies performed on murder victims. It was where the autopsy was conducted on the armed bank robber I shot and killed during a shootout.

It was there at the basement morgue when the medical examiner told me, in detail, that four of the five rounds I fired were fatal rounds. The fifth, the first round I fired in response to him shooting at me, was a shot to the side of the head, caused massive damage, but had that been the only round to have struck him, the shooter/robber may have survived.

A Hanging

In the summer of 1900 Brandt O’Grady was hanged along side Walter Cotton. O’Grady was white and Cotton was black. The hangings were in retaliation for the brutal murder of several individuals.

A mob of citizens, both whites and blacks, stormed the jail and pulled Cotton from his shackles and hanged him from the Cherry tree in the corner of the courthouse yard. Minutes later the black townspeople demanded that O’Grady also be hanged so the group forcefully removed Mr. O’Grady from his cell and “strung him up” on the Cherry tree next to Cotton’s lifeless body.

Inside the old red brick jail in Southside Virginia, the land of cotton, peanuts, and soybeans, were enough tin cups for each prisoner to have one he could call his own, as long as he was serving time there.

When I started working as a sheriff’s deputy, way back during the days of revolvers, patrol cars with those super long whip antennas, and when pepper spray was unheard of, my first assignment was to serve as a jailer. Part of that duty was to oversee the delivery of food trays at mealtimes. Prisoner trustees—short-timers with good jail records— carried the trays from the kitchen to each cell.

The trays we used were the kind you see in school across the country, hard plastic with divided sections that separate each portion of food from another. They were passed to the prisoners through “tray slots” in the cell doors.

At the top right of each tray was a tin cup filled with the beverage du jour. At breakfast time they contained coffee. To accompany lunch and dinner, the beverage was a fruit-flavored drink similar to Kool-Aid.

Prisoners were not allowed to keep the cups inside their cells. To do so was an infraction of jail time which could’ve led to time in “the hole” or a loss of privileges such as visitations, phone use, or their weekly canteen service.

But, inmates will be inmates, and they seemed to find ways to steal a cup or two. The kitchen staff was responsible for the accurate inventory and control of all kitchen items (cups, silverware, trays, etc. Someone was accountable for those items at all times, and it was serious business if something turned up missing. And yes, it’s true. Sometimes those cups were used to bang against the bars. That’s a sound one doesn’t forget too easily.

Tin cups could be fashioned into all sorts of weapons, of course. They were also used for cooking. They’re great for heating coffee, soup, etc., when held over an open fire. Fire, of course, is not permitted at any time. But prisoners find a way. They always seem to find a way to do, well, anything.

My old tired eyes have seen many prisoners over the years, many of whom shared some pretty incredible stories. Some not so true, but others were so fantastic that they manage to flicker cross the front of my mind to this day. I still feel the emotion they exhibited when telling those personal tales.

Those men sipped from their tin cups during holidays, peering out of small, narrow windows, wishing for someone, anyone, to come for a visit. Some drank from the shallow metal cups during their last days on earth, knowing that in just a few hours an executioner would “pull the switch.”

Today, I see my own face in the cup’s reflection, but it’s someone I barely recognize. I’m much older now, but in my mind I’m still the same person who oversaw the delivery of those cups to thirsty prisoners. Many of men were grateful for something as simple as a morning cup of coffee, something we take for granted because we have the opportunity to brew one whenever we like. Not so for the folks who live in captivity.

Yes, the face I see looking back at me is far different than the person who used to peer back at me. Life has moved on and it’s sometimes difficult to let go of the past. But knowing where I’ve been sure goes a long way towards helping me get to where it is I’m going.

Like most things that come and go with the changing of the times, tin cups in jails and prison are likely a thing of the past.

Newcomers to my office barely give my old tin cup a first glance, seeing merely an old and empty, scratched and slightly dented, drinking vessel. Me, I see a tin cup that’s brimming with a lifetime of sorrow, pain, death, misery, happiness, tears, laughter, and more. It’s a cup that runneth over with emotion.

A cup filled with precious memories is what sits in my office. Some good and some not so good. But precious they are. And yes, the cup in my office was once used by murderers, robbers, rapists, and burglars.

Here’s to you.