“I. Know. My. Rights!”

Officers hear those four familiar words many, many times each and every day all across this great land of ours.

It’s a phrase often spoken by the wisest of the wise–the top legal minds of street corners, sour mash-guzzling patrons of back road honky-tonk juke joints, and professional crack and meth smokers everywhere. It’s forcefully uttered by masked basement keyboard warriors who’re out for their weekly brick- and moltov cocktail-throwing adventures, and by pickup truck cowboys out hee-hawing it up after a night of suds-swigging and two-stepping at Myrtle Mae’s Bar and Grill in the strip mall next to the Sizzler turned Bingo Parlor that closed some six years ago.

More times than I care to count, the person delivering the line is a scrawny, wiry sort of guy who prefers to go shirtless, exposing a set of bony ribs that could replace any xylophone in any symphony in the world. They’re the hoodlum wannabes who guzzle three six-packs of cheap beer followed by six shots of Jack Black as a warmup to their serious drinking. Of course, members of all sexes/genders dive in to offer their own spectacular versions of the diatribe and, like the aforementioned folks, they, too, come in all shapes and sizes and from varied backgrounds.

Lately, though, the famous words have been adopted by the likes of soccer moms, college students, sovereign citizens, kids, grocers, butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers.

But no matter from whose lips it crosses, the message is the same, and it’s shouted and screamed and yelled into the faces of law enforcement officers. Of course, the phrase is often followed by a series of threats, such as …

“I. Know. My. Rights, you fat dumbass son of a whore doughnut-eating pig! No offence to pigs, mind you. You work for me. I pay your salary. I’m gonna have your job and I’m gonna sue you and your mama and I’m gonna take your houses and cars and your pension and your mother’s Social Security checks. You gotta let me go. This arrest is illegal ’cause you didn’t read me my rights! Now take off these cuffs … NOW … afore I open a can of whupass on you like you ain’t never seen!!!!”

“I. Know. My. Rights, you fat dumbass son of a whore doughnut-eating pig! No offence to pigs, mind you. You work for me. I pay your salary. I’m gonna have your job and I’m gonna sue you and your mama and I’m gonna take your houses and cars and your pension and your mother’s Social Security checks. You gotta let me go. This arrest is illegal ’cause you didn’t read me my rights! Now take off these cuffs … NOW … afore I open a can of whupass on you like you ain’t never seen!!!!”

Well, Mr. Canary-Chest TinyPants, your legal analysis is incorrect, and your threats of violence against well-armed and well-trained officers do very little to intimidate them. Especially when you’ve shown the world the physical attributes you have to back up those strong promises of ass-whuppins.

So let’s examine TinyPants’ claim regarding Miranda and when it’s required.

Miranda

When is a police officer required to advise a suspect of the Miranda warnings?

I’ll give you a hint, it’s not like we see on television. Surprised?

Television shows often have officers spouting off Miranda warnings the second they have someone in cuffs. Not so. I’ve been in plenty of situations where I chased a suspect, caught him, he resisted, and then we wound up on the ground fighting like street thugs while I struggled to apply handcuffs to his wrists. And yes, words were spoken once I managed to get to my feet, but “Miranda” wasn’t one of them. Too many letters, if you know what I mean. Words consisting of only four letters seemed to flow quite easily at that point.

When Is Miranda Required?

Two elements must be in place for the Miranda warning requirement to apply. The suspect must be in custody and he must be undergoing interrogation.

Writers, this is an important detail – A suspect is in police custody if he’s under formal arrest or if his freedom has been restrained or denied to the extent that he feels as if he’s no longer free to leave.

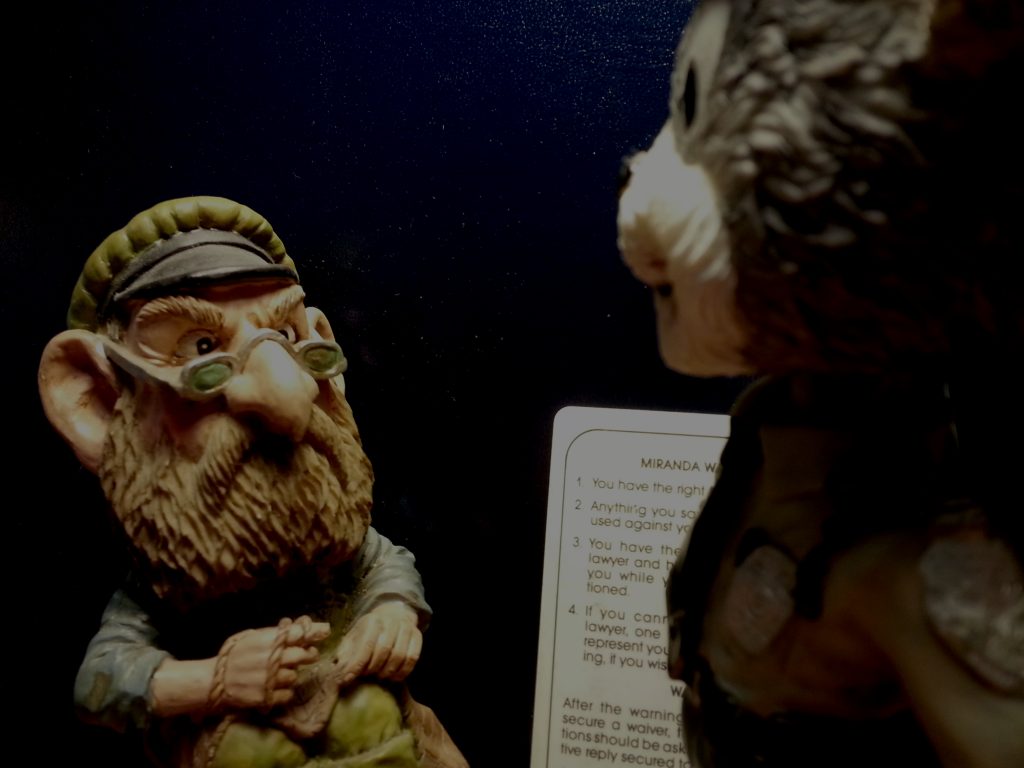

The fellow wearing the handcuffs in the photo below is not free to leave. Therefore, should the officer wish to question him he must advise him of his right to remain silent, etc. However, if the officer decides to not ask questions/interrogate, then Miranda is not required.

I’ve arrested criminals, many of them, in fact, and never advised them of their rights. Not ever. And that’s because I didn’t ask them any questions.

Sometimes officers receive a stack of outstanding arrest warrants for a variety of cases and it’s their job that day to go out and round up those folks. Those officers have no clue as to the circumstances of the crime or case details, therefore they’d not know the appropriate questions to ask. All they know is that the boss handed them a pile of warrants and told them to fetch. This, by the way, is often one of the mundane duties assigned to rookie officers, along with directing traffic and writing parking tickets.

So, the warrant-serving officers locate the person named on the warrant and haul them to the station, or jail, for processing/booking. The officer who had the warrant issued may or may not question the arrested person at a later time. But the arresting officer, the one who played hide and seek with the crook for a few hours on a Monday morning is most likely out of the picture from that point onward. So no questioning = no Miranda.

Interrogation

Interrogation is not only asking questions, but any actions, words, or gestures used by an officer to elicit an incriminating response can be considered an interrogation.

If these two elements are in place officers must advise a suspect of the Miranda warnings prior to questioning. If not, statements made by the suspect may not be used in court. Doesn’t mean the arrest isn’t good, just that his statements aren’t admissible.

Officers are NOT required to advise anyone of their rights as long as they’re not planning to ask questions. Defendants are convicted all the time without ever hearing the police officer’s poem, You Have the Right to …

Miranda facts:

- Officers should repeat the Miranda warnings during each period of questioning. For example, during questioning officers decide to take a break for the night. They come back the next day to try again. They must advise the suspect of his rights again before resuming the questioning.

- If an officer takes over questioning for another officer, she should repeat the warnings before asking her questions.

- Officers may not ask questions if a suspect asks for an attorney.

- If a suspect agrees to answer questions but decides to stop during the session and asks for an attorney, officers must stop the questioning.

- Suspects who are under the influence of alcohol or drugs should not be questioned. Also, anyone who exhibits signs of withdrawal symptoms should not be questioned.

- Officers should not question people who are seriously injured or ill.

- People who are extremely upset or hysterical should not be questioned.

- Officers may not threaten or make promises to elicit a confession.

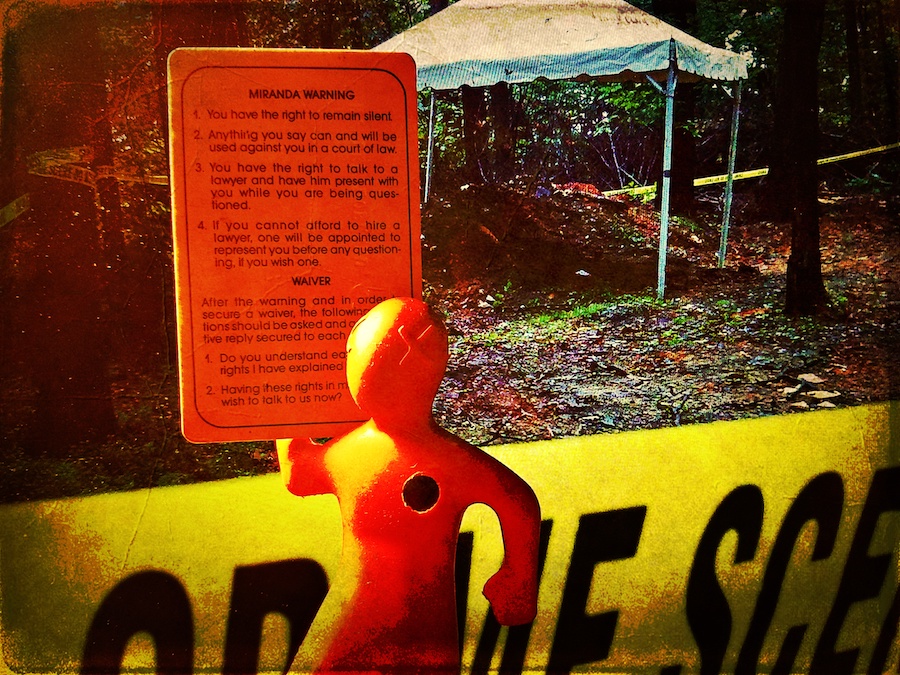

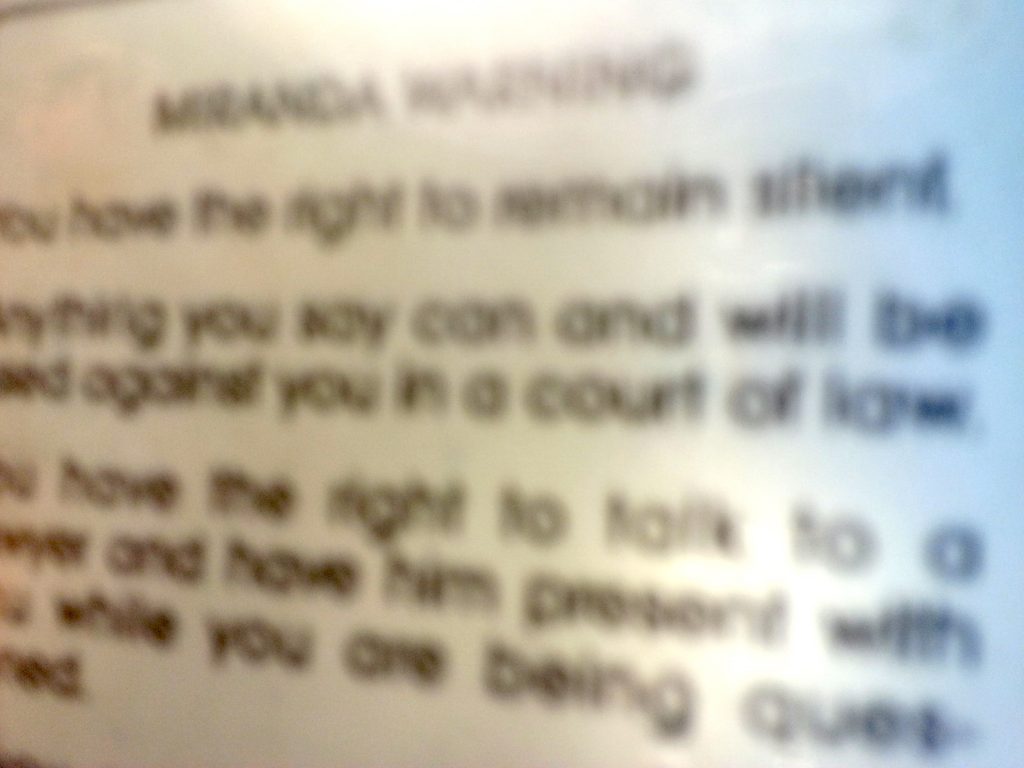

Many officers carry a pre-printed Miranda warning card in their wallets. Here’s a copy of the reverse side of my old Virginia Sheriffs Association membership card (same design, size, and feel of a credit card). I could not begin to count the number of times I’ve used it to read the words to crimincal suspects.

Miranda Card Fact: The Miranda warning requirement stemmed from a case involving a man named Ernesto Miranda. Miranda killed a young woman in Arizona and was arrested for the crime. During questioning Miranda confessed to the slaying, but the police had failed to tell him he had the right to silence and that he could have an attorney present during the questioning. Miranda’s confession was ruled inadmissible; however, the court convicted him based on other evidence.

Fact: The Miranda warning requirement stemmed from a case involving a man named Ernesto Miranda. Miranda killed a young woman in Arizona and was arrested for the crime. During questioning Miranda confessed to the slaying, but the police had failed to tell him he had the right to silence and that he could have an attorney present during the questioning. Miranda’s confession was ruled inadmissible; however, the court convicted him based on other evidence.

Miranda was released from prison after he served his sentence. Not long after his release, he was killed during a bar fight.

His killer was advised of his rights according to the precedent-setting case of Miranda v. Arizona. He chose to remain silent.

Some individual department/location policies require their officers to advise of Miranda at the point of arrest. However, the law does not require them to do so.

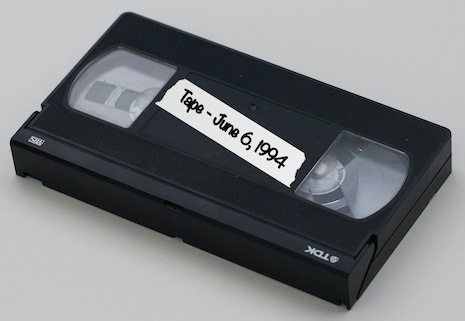

The new label simply read “June 6, 1994.”

The new label simply read “June 6, 1994.”

They simply weren’t talking.

They simply weren’t talking.

Q. Can anyone be trained to be an effective interrogator or are certain inherent personality traits and talents essential for success?

Q. Can anyone be trained to be an effective interrogator or are certain inherent personality traits and talents essential for success?

If the suspect is a green lizard-like man with horns, bumps under the skin where eyebrows should be, head to toe tattoos, and a forked tongue, then the good detective could possibly begin to build rapport by speaking about the silly Bugs Bunny tattoo he’d gotten on his right butt cheek after drinking one too many tequila shots the night of his twenty-first birthday. Doing so could be the ice-breaker needed to start the wagging of Mr. Lizard’s tongue.

If the suspect is a green lizard-like man with horns, bumps under the skin where eyebrows should be, head to toe tattoos, and a forked tongue, then the good detective could possibly begin to build rapport by speaking about the silly Bugs Bunny tattoo he’d gotten on his right butt cheek after drinking one too many tequila shots the night of his twenty-first birthday. Doing so could be the ice-breaker needed to start the wagging of Mr. Lizard’s tongue.

So, try it for yourself. Have your characters “sit” in a chair across from you and then find that one big thing that defines them—the forked tongue or the candy bar and root beer. Then continue to question your “suspect” until you “know” them as a person. You’ll soon find that with each question comes another layer, until soon you have a very real but fictional character sitting across from you. Of course, you may want to do this when no one else is at home to avoid being carted off by the net-wielding folks who run Nervous Hospitals.

So, try it for yourself. Have your characters “sit” in a chair across from you and then find that one big thing that defines them—the forked tongue or the candy bar and root beer. Then continue to question your “suspect” until you “know” them as a person. You’ll soon find that with each question comes another layer, until soon you have a very real but fictional character sitting across from you. Of course, you may want to do this when no one else is at home to avoid being carted off by the net-wielding folks who run Nervous Hospitals.