Have you ever sat in a room designed especially for killing people, looking into the eyes of a serial murderer, watching and waiting for some sign of remorse for his crimes, wondering if he would take back what he’d done, if he could?

Have you ever smelled the searing flesh of a condemned killer as 1,800 volts of electricity ripped through his body, nonstop, for thirty seconds?

Have you ever witnessed a legal homicide carried out by a “man behind the curtain” who, during his career, caused the death of 62 humans who were convicted of their crimes and then received the ultimate punishment, execution. No? Well, twenty-six years ago this month, I sat in a chair just a few feet away from a serial killer and I watched him die a gruesome death. Here are the details.

Timothy Wilson Spencer began his deadly crime spree in 1984, when he raped and killed a woman named Carol Hamm in Arlington, Virginia. Spencer also killed Dr. Susan Hellams, Debby Davis, and Diane Cho, all of Richmond, Virginia. A month later, Spencer returned to Arlington to rape and murder Susan Tucker.

Other women in the area were killed by someone who committed those murders in a very similar manner. Was there a copycat killer who was never caught? Or, did Spencer kill those women too? We’ll probably never learn the truth.

Spencer was, however, later tried, convicted, and sentenced to die for the aforementioned murders. I was selected to serve as a witness to his execution. I accepted, figuring that if I had the power to investigate and arrest someone for capital murder, then I needed to see a death penalty case through to the end.

On the evening of Spencer’s execution, a corrections official met me at the state police area headquarters where I’d parked my unmarked Chevrolet Caprice. It was around 8 p.m. when I climbed into his van, a vehicle typically used for transporting inmates. It had been freshly washed and waxed and the interior was immaculate. The light scent of pine cleaner lingered in the air.

My driver du jour was an always-smiling, short and portly, white-shirt-wearing lieutenant whose skin was the color of caramel. His round head was bare and slick, with the exception of a few small tufts of white hair that brought to mind the fluffy clouds of a summertime sky. He was a friend and sometimes colleague who headed up the prison’s “death squad.” I’d known him for several years and enjoyed his company since his sense of humor was a great match for my own … quirky.

I’d worked with the lieutenant in the past when he approved my request for the loan of several prison K-9s, the nasty, snarling ones that enjoy biting, and their handlers, to assist with a large drug and weapon eradication operation in the city.

During the ride to the prison we occupied our time with small talk and banter about the usual—cop and corrections stuff, and our lives dealing with the worst of the worst. I put them away and he babysat them for the next one to 100 years, or, until the end, which was soon to be for Timothy Spencer.

The lieutenant eventually turned the van onto the long and straight paved road that led to the maximum security compound. The van’s headlamps illuminated a few yards of swampland that flanked the road on both sides. Beyond that … eerie and inky blackness as far as imaginations allowed.

During the approach we passed two groups of people, those who supported the death penalty and those who did not. Many of them carried signs. Some held candles. On the “against” side, a man played a guitar while others swayed from side to side while singing. Some prayed. A minister held both hands above his head while addressing four or five young people, possibly teenagers.

Numerous media vans lined the roadway, with the telescopic antenna standing tall, with cables winding around the poles. Network reporters faced cameras and bright lights while speaking into handheld microphones. One reporter interviewed a visibly angry woman.

A few members of the anti death penalty protestors approached our van and shouted and shook their fists toward it. Others aimed middle fingers at the dark tinted windows. Deputy sheriffs and state troopers, all of whom I knew personally, herded the agitated folks back to their “For” and “Against” roped-off areas.

Finally, after traveling a mile from the main road, bright lights appeared in the sky above the tree line. It was like approaching a sports stadium at night. Then, as if out of nowhere, the prison came into view. It was massive. More inmates lived there than the number of residents in the nearest town.

What looked like miles of a double row of very tall, razor-wire-topped fencing surrounded individual concrete pods designed to house over 500 inmates each. Each housing unit is separated from the others by its own set of fencing. Six 52-foot guard towers were positioned around the perimeter, with heavily-armed officers standing ready as the last means of stopping an escape attempt. The officer in tower one, the nearest to the front gate, stood out on the catwalk holding a rifle, a mini-14/.223, i assumed. It was execution night and everyone was on high alert.

We entered the prison’s interior grounds through the sally port and then through a couple of interior gates, stopping outside a building where I then was escorted to a briefing room where the other execution witnesses sat waiting. The Virginia Department of Corrections’ eastern regional manager stood at the front of the room. Once I was seated he began to explain to our small group what it was we were about to see.

When he was done, we, in single file, were taken to “L” Building, nicknamed “Hellsville” by the inmates. Building “L,” is where death row inmates are brought from death row to await their hour to die. It’s the building where the electric chair and the lethal injection gurney sit quietly until their next time in the spotlight rolls around.

We were seated in a small theater-style room, and much like waiting for a famous play to begin, we all knew the name of the leading man. He was a solo performer who would be dead when the curtain finally closed at the end of the evening.

The room was packed full, a small group consisting of members of the press, two or three attorneys, a few others who’ll remain nameless to respect their privacy, and me, the only cop in the place.

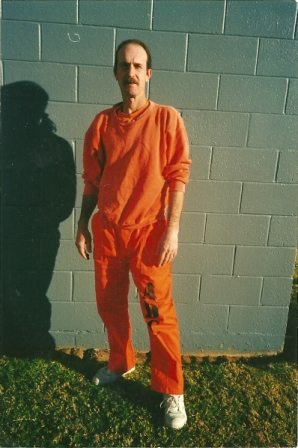

The room where I and the other witnesses sat waiting was inside the death house at Virginia’s Greensville Correctional Center. At the time, the execution chamber was pretty much a bare room made of concrete blocks painted a bright white. Sitting center stage was Old Sparky, the state’s electric chair, an instrument of death that, ironically, was built by prison inmates.

Old Sparky, Virginia’s electric chair.

As part of our duties as official witnesses, we observed a test of the chair which indicated that the chair was in proper working order. To do so, officials placed a resistor across the arms arms of the chair and then connected it to the two electrical cables that would soon be attached to the condemned prisoner. When they switched on the system for the test, a light on the resistor resistor emitted a bright orange glow, then gradually a duller glow. Satisfied that the system was working, we waited.

Timothy Spencer was put to death on April 27, 1994 at 11:13 p.m.

The atmosphere that night was nothing short of surreal. No one spoke. No one coughed. Nothing. Not a sound as we waited for the door at the rear of “the chamber” to open. After an eternity passed, it did, revealing the handful of prison officials who entered first, and then Spencer who walked calmly into the chamber surrounded by members of the prison’s death squad (specially trained, uniformed corrections officers).

I later learned that Spencer had walked the eight short steps to the chamber from a death watch cell, and he’d done so on his own, without assistance from members of the squad. Sometimes the squad is forced to physically deliver the condemned prisoner to the execution chamber.

I cannot fathom what sort mindset it takes to make that short and very final walk. Spencer, though, seemed prepared for what was to come, and he’d made his peace with it. His face was absent emotion. No frown. No tears. No smile. Nothing. He was a man who seemed more like a robot than a human with a beating heart, a thinking brain, and a conscience.

The man who’d brutally and killed so many women, was shorter and a bit more wiry than most people picture when thinking of a serial killer. His head was shaved and one pant leg of his prison blues was cut short for easy access for attaching one of the connections (the negative post, I surmised). His skin was smooth and the color of milk chocolate. Dots of perspiration peppered his forehead and bare scalp like raindrops on a freshly-waxed car.

Spencer looked around the room and the area where we sat. His eyes moved slowly from side to side and up and down, taking in the surroundings and the faces of the witnesses. I wondered if the blonde woman beside me reminded him of either of his victims.

Perhaps the lady in the back row who sat glaring at the condemned killer was the mother of one of the women Spencer had so brutally raped and murdered.

Spencer blinked a bit when looking at the bright overhead lights. Other than that tiny movement his actions were totally and absolutely unremarkable. Had I not know what was about to take place, I’d have assumed he was settling into an easy chair to watch a bit of television before retiring for the evening after a long day at work.

After glancing around the brightly lit surroundings, Spencer took a seat in the oak chair and calmly allowed the death squad to carry out their business of fastening straps, belts, and electrodes. As they secured his arms and legs tightly to the oak chair, he looked on, seemingly uninterested in what they were doing.

I sat directly in front of the cold-blooded killer, mere feet away, separated by a partial wall of glass. His gaze met mine and that’s where his focus remained for the next minute or so. Not even a remote sign of sadness, regret, or fear. Either he was brave, heavily sedated, or stark-raving mad.

The squad’s final task was to place a metal, colander-like hat on Spencer’s head. The cap, like the leg connection, was lined with a brine-soaked sea sponge that serves as an excellent conductor of electricity.

I wondered if Spencer felt the presence of the former killers who’d died in the chair before him—Morris Mason, Michael Smith, Ricky Boggs, Alton Wayne, Albert Clozza, Derrick Peterson, Willie Jones, Wilbert Evans, Charles Stamper, and Roger Coleman, to name a few.

Morris Mason had raped his 71-year-old neighbor. Then he’d hit her in the head with an ax, nailed her to a chair, set her house on fire, and then left her to die.

Alton Wayne stabbed an elderly woman with a butcher knife, bit her repeatedly, and then dragged her nude body to a bathtub and doused it with bleach.

A prison chaplain once described Wilbert Evans’ execution as brutal. “Blood was pouring down onto his shirt and his body was making the sound of a pressure cooker ready to blow.” The preacher had also said, “I detest what goes on here.”

Yes, I wondered if Spencer felt any of those vibes coming from the chair. And I wondered if he’d heard that his muscles would contract, causing his body to lunge forward. That the heat would literally make his blood boil. That the electrode contact points were going to burn his skin. Did he know that his joints were going to fuse, leaving him in a sitting position? Had anyone told him that later someone would have to use sandbags to straighten out his body? Had he wondered why they’d replaced the metal buttons buttons on his clothes with Velcro? Did they tell him that the buttons would have melted?

For the previous twenty-four hours, Spencer had seen the flurry of activity inside the death house. He’d heard the death squad practicing and testing the chair. He’d seen them rehearsing their take-down techniques in case he decided to resist while they escorted him to the chamber. He watched them swing their batons at a make-believe prisoner. He saw their glances and he heard their mutterings.

Was he thinking about what he’d done?

I wanted to ask him if he was sorry for what he’d done. I wanted to know why he’d killed those women. What drove him to take human lives so callously?

The warden asked Spencer if he cared to say any final words—a time when many condemned murderers ask for forgiveness and offer an apology to family members of the people they’d murdered.

The warden asked Spencer if he had any last words. He replied, “Yeah, I think …” He let the word “think” trail away, keeping his thought to himself. Those were the last words spoken by Timothy Spencer, the Southside Strangler. Whatever he’d been about to say, well, he took it with him to his grave.

He made eye contact with me again. And believe me, this time it was a chilling experience to look into the eyes of a serial killer just mere seconds before he himself was killed.

Some of the people in the room focused on the red telephone hanging on the wall at the rear of the chamber—the direct line to the governor—Spencer’s last hope to live beyond the next few seconds. It remained silent.

The warden nodded to the executioner, who, by the way, remained behind a wall inside the chamber, out of our view. Spencer must have sensed what was coming and, while looking directly into my eyes, turned both thumbs upward. A last second display of his arrogance. A death squad member placed a leather mask over Spencer’s face, a mask with only a tiny opening for his nose. Then he and the other team members left the room. The remaining officials stepped back, away from the chair.

Seconds later, the lethal dose of electricity was introduced, causing the murderer’s body to swell and lurch forward against the restraints that held him tightly to the chair.

Suddenly, his body slumped into the chair. The burst of electricity was over. However, after a brief pause, the executioner sent a second jolt to the killer’s body. Again, his body swelled, but this time smoke began to rise from Spencer’s head and leg. A sound similar to bacon frying could be heard over the hum of the electricity. Fluids rushed from behind the leather mask. The unmistakable pungent odor of burning flesh filled the room.

The electricity was again switched off and Spencer’s body relaxed.

It was over and an eerie calm filled the chamber. The woman beside me cried softly. I realized that I’d been holding my breath and exhaled, slowly. No one moved for five long minutes. I later learned that this wait-time was to allow the body to cool. The hot flesh would have burned anyone who touched it.

The prison doctor slowly walked to the chair where he placed a stethoscope against Spencer’s chest and listened for a heartbeat. A few seconds passed before the doctor looked up and said, “Warden, this man has expired.”

That was it. Timothy Spencer, one of the worse serial killers in America’s history was dead, finally.

Outside the prison, Wayne Brown, operations officer at Greensville Correctional Center, delivered a statement to the press. “The man known as the Southside Strangler was pronounced dead at 11:13 p.m., ” said Brown.

Strange, but true facts about Spencer’s case:

– Spencer raped and killed all five of his victims while living at a Richmond, Virginia halfway house after his release from a three-year prison sentence for burglary. He committed the murders on the weekends during times when he had signed out of the facility.

– Spencer was the first person in the U.S. executed for a conviction based on DNA evidence.

– David Vasquez, a mentally handicapped man, falsely confessed to murdering one of the victims in the Spencer case after intense interrogation by police detectives. He was later convicted of the crime and served five years in prison before DNA testing proved his innocence. It was learned that Vasquez didn’t understand the questions he’d been asked and merely told the officers what he thought they wanted to hear.

– Spencer used neck ligatures to strangle each of the victims to death, fashioning them in such a way that the more the victims struggled, the more they choked.

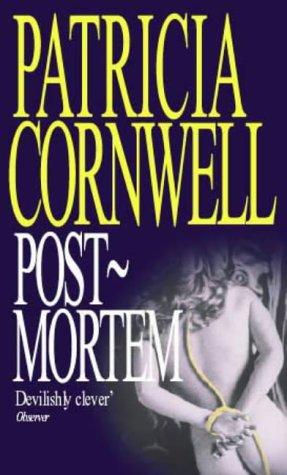

– Patricia Cornwell’s first book, Post Mortem, was based on the Spencer murders.

Jerry Givens, a former executioner for the Commonwealth of Virginia—the man who executed Timothy Spencer—described his opinion of the death penalty when he said, “If I execute an innocent person, I’m no better than the people on death row.”

Givens, after executing 62 people, now strongly opposes the death penalty.

And then there are the cases of the men and women on death row who’ve been exonerated based on evidence that proved that didn’t or couldn’t have committed the crime of which they were accused and convicted. Such as Ray Krone, a friend of this site who spent nearly a decade on death row before DNA evidence proved his innocence.

Ray detailed the experience in an article for this blog. To read his story please click here.

Next comes bite-mark evidence. Not so long ago, within the past couple of years, the Presidents Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) announced that forensic bite-mark evidence is not scientifically valid, nor is it likely to ever be validated. In other words, more junk science (skin may move after death during decomposition, skin and flesh are not stable material—may not hold a precise pattern, etc.).

Next comes bite-mark evidence. Not so long ago, within the past couple of years, the Presidents Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) announced that forensic bite-mark evidence is not scientifically valid, nor is it likely to ever be validated. In other words, more junk science (skin may move after death during decomposition, skin and flesh are not stable material—may not hold a precise pattern, etc.). A few weeks ago, my girlfriend Cheryl read a novel by

A few weeks ago, my girlfriend Cheryl read a novel by