In the days before DNA testing became available for use in criminal cases, cops, prosecutors, judges, and juries relied on other physical evidence to send bad guys to jail—fingerprints and footprints, soil, glass fragments, trace evidence, etc. Those things along with confessions and eyewitness testimony were the building blocks used to convict the guilty.

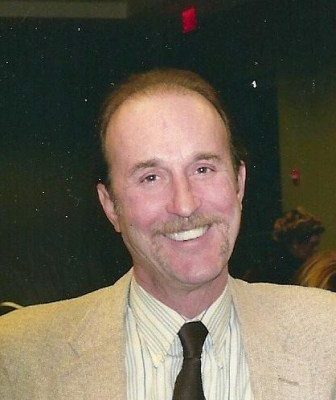

Then, when DNA arrived on the scene, well, it soon became apparent that somehow officials had made a few boo-boos along the way and had sent more than a handful of innocent men and women to jail for crimes they didn’t commit. DNA testing of old evidence, in fact, exonerated people like our friend Ray Krone who served ten years in prison, three of which were on death row, for a murder he didn’t and couldn’t have committed.

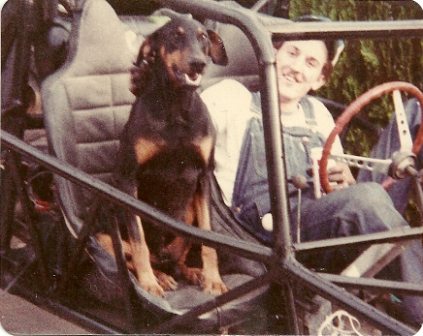

Ray as an inmate at Arizona State Prison in Yuma

Ray Krone could’ve easily been eliminated as a suspect had DNA testing been conducted at the time of the investigation. Instead, his conviction was based on bite mark evidence, a test/examination/comparison method that’s been found to be unreliable.

DNA test results were used in court cases as early as the mid 1980s. Ray was convicted in the early 90s, without the benefit of DNA testing, a simple test that would have prevented him from serving time in prison as an honest, clean-handed man.

Nowadays, to weed out the innocent, DNA testing is routinely performed in the early stages of criminal investigations. And it helps … some. The use of DNA tests in post-conviction cases and appeals sometimes leads to exonerations, such as, for example, Ray Krone’s release from prison.

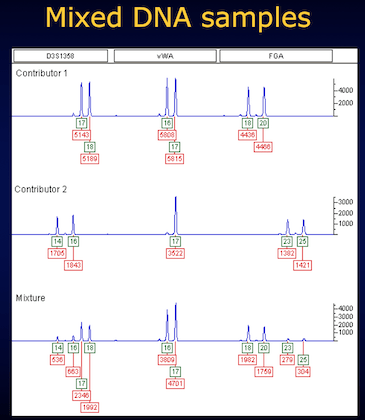

Electropherogram – a chart produced by testing equipment after DNA sequencing is completed.

Unfortunately, and what most members of juries do not understand, is that during a typical criminal investigation, in only about 10-20 percent of all cases do cops find testable biological evidence. In spite of this low percentage, some juries still expect a case to hinge on DNA results. However, without something to test, of course, there’ll be no electropherograms pointing to a specific suspect.

Sometimes, even with the presence of DNA, those results are not always definitive.

Electropheragram showing tested DNA of two subjects, and a mixture of DNA collected from a victim. Results showing a mixture make it difficult to point to any one suspect.

But let’s go back to the 10-20 percent figure, the number of cases where testable biological evidence is located and collected by investigators and then subsequently tested by laboratory scientists and other experts.

At the upper end, the 20 percent range, that leaves 80 percent of all criminal cases that are solved by using other means of crime-solving, such as the aforementioned fingerprints and footprints, soil, glass fragments, trace evidence and, of course, detectives going about the business of good old-fashioned door-knocking and talking to people. The combination of the physical evidence and confessions and eyewitness testimony is what leads to the majority of criminal convictions.

Sadly and dismally disastrous, without mostly foolproof scientifically tested evidence, courts must rely on human testimony, humans whose memories often fluctuate. Police investigators who enter a crime scene with a serious and dreaded case of tunnel vision. Prosecutors who do the same once the already skewed/tunnel-vision-tainted, unreliable witness’ flawed statement evidence is presented to them,

Overworked and underpaid public defenders aren’t always up to date on current scientific practices and the laws governing them. Those same attorneys carry heavy caseloads which stretches their time to a breaking point so thin that they can’t possibly devote the amount of time needed to decently defend their appointed clients. Their budgets are minimal, meaning expensive testing and other necessities for their clients’ defenses are practically nonexistent.

Post-conviction procedures (motion for new trials, ineffective assistance of council, appeals to address the lack of scientific testing to prove innocence) are a huge uphill climb for people who’ve been incarcerated. This is especially so for the poor.

Those of meager means often have no alternative other than to wade through prison law libraries, hoping to make sense of the legal jargon that fits their situation. They sometimes employ a jailhouse lawyer to help, paying for his services by whatever means available—cleaning his cell, cooking meals, shining shoes, and even purchasing items for them from the commissary, or having family members on the outside send money to the amateur legal eagle.

The wealthy, of course, have outside resources to help with the filing of necessary paperwork. But there’s sometimes a bad egg in this bunch, such as the high-priced, fancy-smancy defense attorney I overheard telling his client who’d just received 37 months in federal prison for possessing crack cocaine worth little more than $100, that for an additional $25,000 he could arrange to have him serve less time on home confinement. That’s fair, right?

And, there’s the Innocence Project who helps the wrongly convicted.

Aside from the obvious, there’s a real problem with the aftermath that’s sure to arise after retroactively clearing prisoners of their crimes based on DNA evidence.

Yes, when all the dust settles after all the men and women who’ve been wrongfully convicted and then cleared by the use of DNA evidence are out of prison with their recoreds expunged and their names cleared, there will still be hundreds if not thousands of people still behind bars because their convictions were based on the bad memory of a witness, a cop or prosecutor with tunnel vision, being in the wrong place at the wrong time, a mistake made at the lab during evidence analysis (mislabel an item, etc., tainted evidence, such as the accidental transfer of a fingerprint or even DNA evidence).

Someday soon there will be a false sense that DNA has cleared ALL the innocent people, leaving those behind who surely must be guilty of their crimes because there was no scientific evidence to prove otherwise. But we know this can’t be so. Why not? Because of human error.

Yes, it is indeed possible to transfer a fingerprint, even accidentally.

Tertiary DNA Transfer

It’s possible that DNA can be accidentally transferred from one object to another. A good example could be the killer who shares an apartment with an unsuspecting friend. He returns home after murdering someone and then tosses his blood-spatter-covered shirt into the washer along with his roommate’s clothing. The machine churns and spins through its wash cycles, an action that spreads the victim’s DNA throughout the load. Police later serve a search warrant on the home, seize the clothing, and discover the victim’s DNA on the roommate’s jeans. The innocent roommate is arrested for murder.

The list of human error possibilities is extremely long and, unfortunately, there’s no magic DNA bullet to help clear the innocent folks convicted based on an accident. Their battles are practically hopeless. Laws and courts make it nearly impossible for people already serving time to have a judge revisit their cases.

Odds are, that hopelessness follows a few of the condemned all the way to the execution chamber, where it is indeed conceivable that an innocent man could be, and most likely has been, put to death.

And, well, I suppose it’s possible that given the right/wrong circumstances, anyone, even you, could find themselves behind bars for a crime they didn’t commit.

Next comes bite-mark evidence. Not so long ago, within the past couple of years, the Presidents Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) announced that forensic bite-mark evidence is not scientifically valid, nor is it likely to ever be validated. In other words, more junk science (skin may move after death during decomposition, skin and flesh are not stable material—may not hold a precise pattern, etc.).

Next comes bite-mark evidence. Not so long ago, within the past couple of years, the Presidents Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) announced that forensic bite-mark evidence is not scientifically valid, nor is it likely to ever be validated. In other words, more junk science (skin may move after death during decomposition, skin and flesh are not stable material—may not hold a precise pattern, etc.). A few weeks ago, my girlfriend Cheryl read a novel by

A few weeks ago, my girlfriend Cheryl read a novel by