The transition from working the streets as a patrol officer to the coat and tie sleuthing of a police detective can be somewhat of an eye-opener. While definitely closely related, the two jobs differ.

Patrol officers are typically responsible for responding to crimes that have either recently occurred or are in progress. Detectives are usually called upon to investigate crimes and crime scenes, those encountered by patrol officers, and sometimes medical examiners or coroners. Of course, it’s not at all unusual for cases to arise from reports by citizens, or as the result of information gained while investigating an altogether different crime.

For example, while collecting evidence at the murder scene of a low level drug dealer, detectives discover a large stash of stolen guns, and cash stained with the red dye used by banks to help track bank robbers. Fingerprints on many of the guns belong to four known criminals, two of which have served time for bank robberies. As a result, detectives are able to solve a couple of major cases in addition to the homicide, the original case.

As a patrol officer, much of the initial work is conducted in a rush due to the immediate need to focus on and react to action-based events as they unfold—the then and now. Detectives, on the other hand, examine a much broader perspective once the “heat of the moment” has cooled to a slower pace. Ordinarily, investigators have the time to map out a solid plan of action and to organize that process.

This, the sudden shift from patrol to investigations, can sometimes be a bit difficult. It’s tough to slow your pace when all you’ve known is to work at a rapid, adrenaline-fueled clip day-in and day-out. It’s lights and sirens and speed and struggling with combative suspects, car chases, and shootouts, to an immediate slowdown. It’s a shock to the mind and body.

No more rushing to he-said she-said calls. No more traffic summons to write. No more barking dogs or loud music complaints. And No More Graveyard Shifts!

Even the paperwork involved in the two duties differs. Patrol officers complete many simple “fill in the blanks” forms—speeding tickets, breath tests, incident reports, etc.—and perhaps anywhere from a brief paragraph to a page or two of narrative explaining the details of the calls to which they’ve responded during their shifts. And, of course, the notes they’ll use for court testimony and to brief detectives who’ll further investigate major crimes.

In contrast, the amount of paperwork required of detectives can sometimes involve case notes chronicling criminal activity and evidence for periods of a year or more. Detectives are also responsible for composing affidavits and search warrants.

A savvy detective examines ALL pertinent evidence. They’ll brainstorm with other detectives. They’ll question everyone who may be able to shed even a sliver of light on the case. And they document EVERYTHING, and then check and double-check to be sure that no stone is left unturned.

Little by little detectives chisel and whittle away at a case until all the unnecessary and irrelevant bits are out of the way. Then, all that remains is the name of the perpetrator. It’s sort of like pouring all evidence into a large funnel where it swirls and twirls around until it reaches the bottom where out pops your suspect, ready for handcuffing. Obviously crime-solving is not that simple, but the analogy sort of fits.

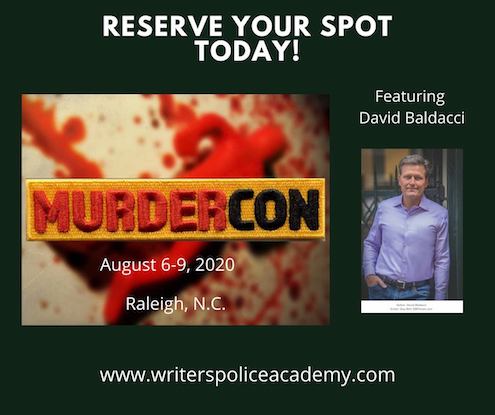

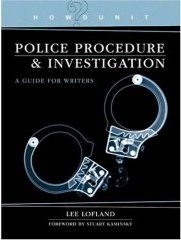

My publisher once posted an excerpt from my book about police procedure. The segment is about my thoughts on becoming an investigator, the intro to the chapter devoted to detectives.

I thought it might be fun to share it with those of you who haven’t read the book. Those of you who have read the book, well, we can chat about something else while the others are reading.

From Chapter Four:

Detectives usually begin their careers as uniformed police officers who work their way up the chain of command, striving to obtain either the position of a uniformed supervisor or move into what some officers think of as the ultimate police job – a detective.

How an officer becomes a detective varies with each individual department. Some departments offer the position as a promotion. These departments post the vacant position and officers apply and test for the job, and the most qualified person receives the advancement. Promotions, or assignments to a detective division, aren’t normally awarded to officers until they’ve completed at least five years of service. Other departments take the rivalry between uniformed officers and the plainclothes detectives into account and simply assign officers to a detective’s position on a rotating basis, which allows every officer a turn as an investigator.

A detective is responsible for the investigation of both misdemeanor and felony crimes. How each department carries out these investigations depends upon the size of the department. Some departments are large enough to have detectives who specialize in certain areas such as credit card fraud, homicide, juvenile crime, arson, narcotics, rape, vice, etc. (We’ll look at some of these areas in greater detail later in the chapter.) Detectives sometimes work in several specialized areas before finding one they like. Once they do, they usually make that area their permanent assignment.

Other departments have only a couple of detectives for the entire agency – if any. In some rural departments where manpower is limited, patrol officers serve as first responders, evidence technicians, and investigators. There are advantages to each situation. The specialized detective becomes very skilled at his particular craft, whereas a detective or patrol officer in a smaller department has the opportunity, out of necessity, to work all kinds of cases.

No matter what the assignment, the duties are the same. Detectives are investigators who gather facts and collect evidence in criminal cases. They conduct interviews and interrogations, examine records and documents, observe the activities of suspects, and participate in and conduct raids or arrests. A detective is usually charged with applying for and obtaining search warrants. To accomplish these tasks effectively, detectives are trained with a more diverse approach than patrol officers.

Both detectives and patrol officers are required to attend, at minimum, semiannual in-service training to stay abreast of new laws and procedures. In addition to the in-service training, a detective’s education must be endlessly updated, and his base of knowledge must be constantly expanded. Criminals are continually developing new ideas and methods to get around the law, and the detective has to make every effort to stay one step ahead of them.

Modern criminals are more highly educated than offenders of the past, and today’s crooks rehearse and practice every aspect of their craft, like actors studying for a Broadway production. The thugs even hone their shooting skills. I was once searching the trunk of a drug dealer’s vehicle and found an automatic weapon, several rounds of ammunition, and a police silhouette target. The center of the target was filled with bullet holes, and Lee Lofland was written above the head. That was an eye-opener.

There are many new ways to fight crime in today’s computer and technology age, but nothing can compare to the old-fashioned method of the detective getting out and beating the streets for information and clues.

The image of the detective has changed as well. It has evolved from the trench-coat-wearing sleuth to a more stylishly dressed investigator. That image possibly reflects a larger clothing allowance than was once provided by departments. I think, years ago, I wore the long coat not because I was cold, but to cover my outdated cheap suits. All my sport coats had torn linings from years of friction caused by my gun’s hammer constantly rubbing against the fabric. When I began my career, the pay was around 8,400 dollars annually, with no clothing allowance. Also in those days, we had to buy our own guns, handcuffs, flashlights, raincoats, ticket books, and shoes. Oh yeah, and bullets. If we thought we might need them, we purchased a handful of those as well.

Today, all expenses are paid by the officer’s department, including clothing allowances for undercover officers who sometimes must wear really unusual clothing in order to blend in with their working environment.

A case begins with the commission of a crime. Uniformed patrol officers are often the first officers on the scene, and they gather the pertinent information-the who, what, where, why, when, and how, if available. It’s the duty of the uniformed patrol officer to secure the scene until a detective or the officer in charge relieves him. The officer who gathers the information later passes it on to the detective assigned to the case. Cases are usually assigned on a rotating basis, or a detective can be assigned to a particular case based on her particular knowledge and skills that relate to the offense. Once assigned to a case, a detective will follow it through until the case has been solved and the suspect is tried and convicted. The detective may use other officers to assist in the investigation, but the case will remain in her charge.

Fact gathering is a must in police work. Detectives can only relate specific details in a court of law and may not offer opinion, as a rule, for testimony. However, during the investigation, gut feelings and instinct play a large role in the detective’s search for information. Years of experience can be, and often are, the most formidable tool in the detective’s arsenal.

IN THE LINE OF DUTY: ON BECOMING A DETECTIVE

Note: These In The Line Of Duty headings appear a few times throughout the book. They’re my real-life reflections of something that actually happened to me while I was on the job.

When I raised my right hand to take the oath to serve my state and my country, I felt a lump rise in my throat. It was such an honor and a thrill to finally be sworn in as a police officer. The feeling of putting on a uniform and pinning a shiny, silver badge to my chest was one of the greatest moments of my life. When the day finally arrived, though, to transition from a uniformed officer to a plainclothes detective, I couldn’t wait to trade the uniform for a new suit and to hook a new, gold badge on my belt. After all, my childhood dream was to become an investigator, and I could finally wear cotton again instead of double-knit polyester shirts with fake buttons that zipped up the front and pants that retained enough heat to bake bread. (Of course, that cool stripe down the leg offset all negatives!)

I turned in my marked patrol vehicle and received my first department-issued, unmarked car. It was an old, beat-up Chevrolet Caprice, a car I write about fondly in my books and stories. The car was midnight blue, several years old, and would reach its top speed of eighty-five miles per hour only after going downhill for about three miles. I didn’t care. It was mine. I washed it, cleaned the tires and wheels, and put my things-a fishing-tackle box filled with fingerprint equipment, a shotgun with an eighteen-inch barrel, extra ammo, hand cleaner, paper towels, and a roll of crime scene tape-into the trunk. I’d get more tools later as I figured out what I needed. For now, I was ready for my first case.

In my early days as a patrol officer, I looked on with envy as the detectives came in and took over my cases after I’d done the dirty work. They were the guys getting their pictures in the newspapers and getting all the glory for doing nothing … or so I thought. It took just a few months of being a detective to dream of an eight-hour shift, like the old days, instead of a twenty-hour day, and of not being called out in the middle of the night, every night! The thought had never occurred to me that it would be irritating to have newspaper reporters snapping photos of me while I struggled to hold in my lunch at a gruesome homicide scene, or that reporters would write things in the paper I didn’t say or leave out the important things I did say.

Nobody teaches you how alienated you become from your old co-workers, the boys in blue, once you become a detective. Uniformed officers sometimes feel a bit of jealousy toward detectives, and detectives sometimes experience a bit of an unjustified superiority complex toward uniformed officers. It’s a rivalry that’s always been in place and probably always will be.

Nobody explains the many hours you’ll spend sitting in the woods, or in the bushes, with hungry mosquitoes and spiders and snakes, or in the rain or snow, watching suspects in your attempts to build cases. Nobody tells you how it feels to work undercover and to walk into the middle of a drug deal, unarmed and without a radio. Nobody describes how it feels to be shot at, spit on, beat up, kicked, scratched, stabbed, cut, knocked down, punched, and pepper sprayed (with your own pepper

spray), all the while wearing a suit.

Yes, I was finally a detective and it was absolutely … glorious!

Marriage is practically taboo in crime fiction. Rarely do fictional law enforcement officers enjoy the company of spouses or serious relationships. Yes, some are haunted by the tormented spirits of dead husbands or wives, but not living, breathing people. I suppose it’s easier to write a tale about a person who’s single, but cops in the real world do indeed marry, and some do so four or five times since the job truly can wreak havoc on married life. For the most part, though, family life is important.

Marriage is practically taboo in crime fiction. Rarely do fictional law enforcement officers enjoy the company of spouses or serious relationships. Yes, some are haunted by the tormented spirits of dead husbands or wives, but not living, breathing people. I suppose it’s easier to write a tale about a person who’s single, but cops in the real world do indeed marry, and some do so four or five times since the job truly can wreak havoc on married life. For the most part, though, family life is important. There you go, eight pet peeves of many cops who

There you go, eight pet peeves of many cops who

Denene Lofland, PhD, FACSc, is an expert on bioterrorism and microbiology. She’s managed hospital laboratories and for many years worked as a senior director at biotech companies specializing in new drug discovery. She and her team members, for example, produced successful results that included drugs prescribed to treat cystic fibrosis and bacterial pneumonia. Denene, along with other top company officials, traveled to the FDA to present those findings. As a result, those drugs were approved by the FDA and are now on the market.

Denene Lofland, PhD, FACSc, is an expert on bioterrorism and microbiology. She’s managed hospital laboratories and for many years worked as a senior director at biotech companies specializing in new drug discovery. She and her team members, for example, produced successful results that included drugs prescribed to treat cystic fibrosis and bacterial pneumonia. Denene, along with other top company officials, traveled to the FDA to present those findings. As a result, those drugs were approved by the FDA and are now on the market.