Law enforcement officers collect a variety of evidence at crime scenes, such as bullet fragments, weapons, narcotics, and fingerprints. In addition, police gather body fluids, skin cells, bones, and hairs, hoping that one or more of those substances will contain a suspect’s DNA.

But where, you might ask, is the DNA located? Well, it’s certainly not doing the backstroke in the pool of blood that leaked from a fallen victim of a gunshot. Instead, the DNA evidence sought by police—nuclear DNA—is contained within the nuclei of cells.

Cells, the Home of Nuclear DNA

All cells in our body are made up of a cell wall (cell membrane), cell fluid (cytoplasm) and a nucleus, with the exception of red blood cells and platelets. Since neither of latter two have a nucleus they do not contain DNA.

Nuclear DNA is made up of genetic material from our fathers and mothers. The nucleus of each cell contains a pair of chromosomes—, one from each parent.

Each cell typically contains 23 pairs of chromosomes, for a total of 46. Twenty-two of the pairs are called autosomes, and they look identical in both male and female humans. The 23rd pair are the sex chromosomes and they are distinctly different between males and females. Females have two copies of the X chromosome. Males have one X and one Y chromosome.

As evidence in criminal matters, DNA serves a dual purpose—identifying an individual as the source of the DNA found on an evidence item, or to exclude the individual as the contributor of the collected DNA evidence.

Now, we’ve briefly and generally discussed that DNA lives in cells, and those cells are where scientist go to retrieve the DNA needed for testing. And we know that DNA is readily found in body fluids, skin cells, bones, and for many years it was believed that testing hair for DNA was only possible if the bulb/root at the base of the hair shaft was intact. This was so because the keratinization process that creates the hair shaft during its growth often breaks down (lyses ) cell membranes.

DNA IS present, though, in hair shafts, but in small quantities. It’s quite short and fragmented, which is similar to DNA found in ancient remains. So yes, like testing DNA found remains of wooly mammoths and other beings and bits and bobs from long ago, it is possible to isolate nuclear DNA from rootless human hair samples.

In fact, to make this possible, a company called InnoGenomics uses a magnetic bead extraction system that’s specifically optimized for the process of capturing low-level, highly degraded DNA.

By combining InnoGenomics’ two DNA typing kits together—InnoXtract and InnoTyper 21 (IT21), the isolation and typing of nuclear DNA from rootless hair shafts is quite achievable. And, the process is compatible with Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) instruments, such as Promega’s Spectrum CE System.

So yes, crime writers, the heroes of your tales have a tool to add to their crimefighting toolboxes, because it is indeed possible to obtain nuclear DNA from hair shafts.

DNA Testing in General

The first step in the testing process is to extract DNA from the evidence sample. To do so, the scientist adds chemicals to the sample, a process that ruptures cells. When the cells open up DNA is released and is ready for examination.

Did you know it’s possible to see DNA with the naked eye? Well, you can, and at the bottom of this page you’ll learn how see the DNA that you, in your home kitchen, can extract DNA from split peas.

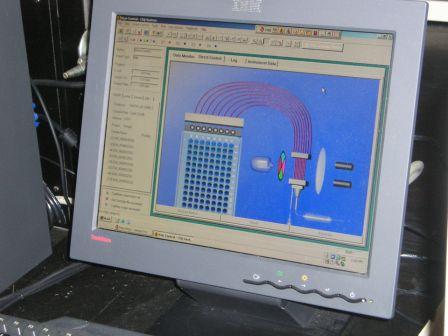

After DNA is extracted it’s then loaded into wells inside the genetic analyzer.

Scientist placing a well plate containing 96 individual wells into a genetic analyzer. Below right in photo is a closeup of a well plate.

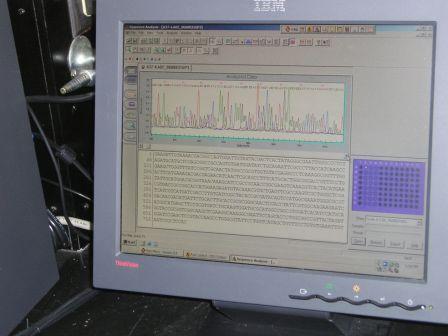

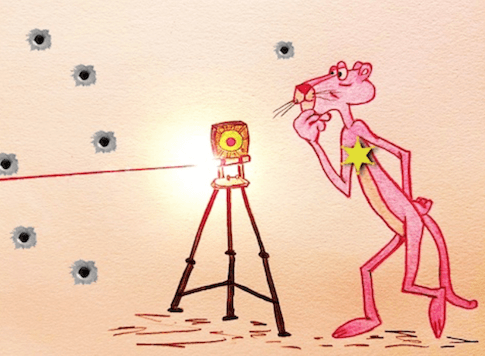

Electric current separates the DNA, sending it from the wells through narrow straw-like tubes called capillaries. During its journey through the analyzer, DNA passes by a laser. The laser causes the DNA loci (a gene’s position on a chromosome) to fluoresce as they pass by, which allows a tiny camera to capture their images.

The image below shows DNA’s path from the wells through the capillaries past the laser.

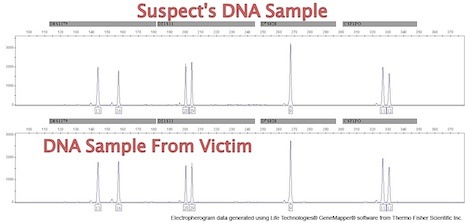

At the end of the testing, the equipment produces a graph/chart called an electropherogram, a chart/graph of peaks and valleys that precisely pinpoints where genes are located.

An allele is a term that describes a specific copy of a gene. Each allele occupies a specific region on the chromosome called a gene locus. A locus (loci, plural) is the location of a gene on a chromosome.

Peaks on the graph depict the amount of DNA strands at each location (loci). It is this unique pattern of peaks and valleys that scientists use to match or exclude suspects.

The image below, as ominous as it appears, is an electropheragram showing the DNA of a strawberry.

Serial Killer Challenges DNA Results

*The following text regarding the appeal from serial killer Timothy W. Spencer, The Southside Strangler,” is from the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Spencer’s case was the first in the U.S. based on DNA evidence that resulted in the death penalty. I served as a witness to Spencer’s execution. Click here to read about my experience.

“Timothy W. Spencer, Petitioner-appellant, v. Edward W. Murray, Director, Respondent-appellee, 5 F.3d 758 (4th Cir. 1993)

US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit – 5 F.3d 758 (4th Cir. 1993)Argued Oct. 28, 1992. Decided Sept. 16, 1993

J. Lloyd Snook, III, Snook & Haughey, Charlottesville, VA, argued (William T. Linka, Boatwright & Linka, Richmond, VA, on brief), for petitioner-appellant.

Donald Richard Curry, Sr. Asst. Atty. Gen., Richmond, VA (Mary Sue Terry, Atty. Gen. of Virginia, on brief), for respondent-appellee.

Before WIDENER, PHILLIPS, and WILLIAMS, Circuit Judges.

OPINION

WIDENER, Circuit Judge:

Timothy Wilson Spencer attacks a Virginia state court judgment sentencing him to death for the murder of Debbie Dudley Davis. We affirm.

The gruesome details of the murder of Debbie Davis can be found in the Supreme Court of Virginia’s opinion on direct review, Spencer v. Commonwealth, 238 Va. 295, 384 S.E.2d 785 (1989), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 1093, 110 S. Ct. 1171, 107 L. Ed. 2d 1073 (1990). For our purposes, a brief recitation will suffice. Miss Davis was murdered sometime between 9:00 p.m. on September 18, 1987 and 9:30 a.m. on September 19, 1987.

Miss Davis was murdered sometime between 9:00 p.m. on September 18, 1987 and 9:30 a.m. on September 19, 1987. The victim’s body was found on her bed by officers of the Richmond Bureau of Police. She had been strangled by the use of a sock and vacuum cleaner hose, which had been assembled into what the Virginia Court called a ligature and ratchet-type device. The medical examiner determined that the ligature had been twisted two or three times, and the cause of death was ligature strangulation. The pressure exerted was so great that, in addition to cutting into Miss Davis’s neck muscles, larynx, and voice box, it had caused blood congestion in her head and a hemorrhage in one of her eyes. In addition her nose and mouth were bruised. Miss Davis’s hands were bound by the use of shoestrings, which were attached to the ligature device. 384 S.E.2d at 789.

Semen stains were found on the victim’s bedclothes. The presence of spermatozoa also was found when rectal and vaginal swabs of the victim were taken. In addition, when the victim’s pubic hair was combed, two hairs were recovered that did not belong to the victim. 384 S.E.2d at 789. The two hairs later were determined through forensic analysis to be “consistent with” Spencer’s underarm hair. 384 S.E.2d at 789. Further forensic analysis was completed on the semen stains on the victim’s bedclothes. The analysis revealed that the stains had been deposited by a secretor whose blood characteristics matched a group comprised of approximately thirteen percent of the population. Spencer’s blood and saliva samples revealed that he is a member of that group. 384 S.E.2d at 789.

Next, a sample of Spencer’s blood and the semen collected from the bedclothes were subjected to DNA analysis. The results of the DNA analysis, performed by Lifecodes Corporation, a private laboratory, established that the DNA molecules extracted from Spencer’s blood matched the DNA molecules extracted from the semen stains. Spencer is a black male, and the evidence adduced at trial showed that the statistical likelihood of finding duplication of Spencer’s particular DNA pattern in the population of members of the black race who live in North America is one in 705,000,000 (seven hundred five million). In addition, the evidence also showed that the number of black males living in North America was approximately 10,000,000 (ten million). 384 S.E.2d at 790.”

People who suffered from excessive fluid build-up decompose faster than those who were dehydrated. And people with massive infections and congestive heart failure will also decompose at a more rapid rate than those without those conditions.

People who suffered from excessive fluid build-up decompose faster than those who were dehydrated. And people with massive infections and congestive heart failure will also decompose at a more rapid rate than those without those conditions.

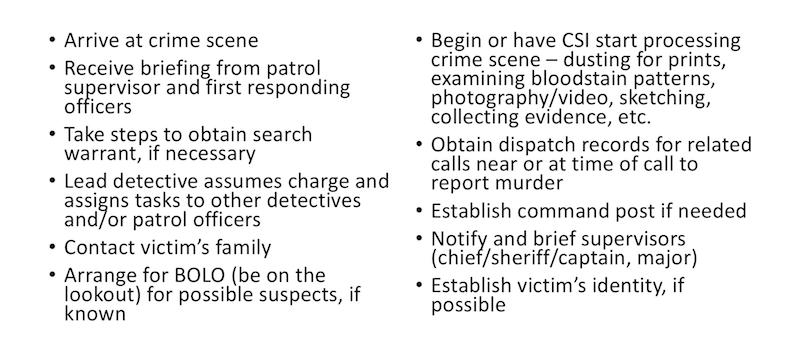

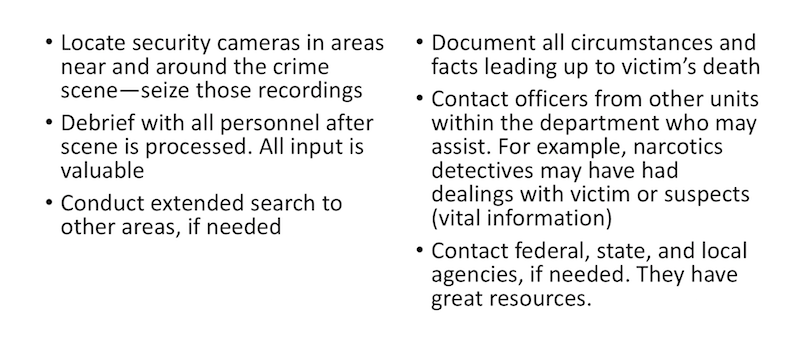

Crime Scene and scene of the crime are not always synonymous. A crime scene is anywhere evidence of a crime is found (a dumpster located five miles away where a killer dumped the murder weapon, or the killer’s home where he deposited his bloody clothes, where the body was found if removed from the scene of the crime, etc.). Scene of the Crime is the location where the actual crime took place (where the killer actually murdered his victim).

Crime Scene and scene of the crime are not always synonymous. A crime scene is anywhere evidence of a crime is found (a dumpster located five miles away where a killer dumped the murder weapon, or the killer’s home where he deposited his bloody clothes, where the body was found if removed from the scene of the crime, etc.). Scene of the Crime is the location where the actual crime took place (where the killer actually murdered his victim).

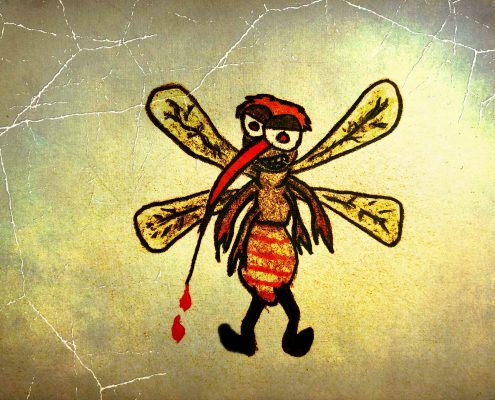

A quick DNA test of the blood found in the belly of the bug could quite easily reveal the name of the killer (if his information is in the system), and how cool would it be to bring in Mr. I. Done Kiltem and notice he has a fresh mosquito bite on his cheek? I know, right?

A quick DNA test of the blood found in the belly of the bug could quite easily reveal the name of the killer (if his information is in the system), and how cool would it be to bring in Mr. I. Done Kiltem and notice he has a fresh mosquito bite on his cheek? I know, right?