Experts are often asked what kinds of entrance and exit wounds are produced by various types of ammunition. The answers to those questions are simple … it depends.

The rounds in the photograph below feature hollow point bullets similar to the rounds fired from the Thompson sub-machine gun I’m holding in the top and quite ancient photo. I pulled the picture from the buried crypt where I keep my old cop stuff.

The .45 caliber rounds above are approximately the diameter of the Sharpie pens many authors use to sign books. That’s pretty close to the size of most entrance wounds inflicted when .45 caliber rounds pierce the flesh.

Pictured below is an entrance wound caused by 9mm round at point blank range, a close contact gunshot wound. Obviously, this was a fatal wound since I took this picture during the autopsy of the victim. Note the post-autopsy stitching of the “Y” incision (above right of the photo).

Also notice the charred flesh around the wound. This was caused by the heat of the round and burning powder as it contacted the victim’s skin. The bruising around the wound was, of course, caused by the impact.

9mm bullet wound to the chest—close range.

Next is one of the .45 rounds after it was fired from a Thompson machine gun.

Firing the Thompson at a sheriff’s office indoor range in Ohio. Notice the piece of ejected brass to the right of the major’s arm. I took the photo and was lucky enough to capture the shot of the brass casing during its fall to the floor.

The round passed through the paper target, through several feet of thick foam rubber, through the self-healing wall tiles of the firing range, and then struck the concrete and steel wall behind the foam. The deformed bullet finally came to rest on the floor. Keep in mind, though, that this all occurred in the blink of an eye, or quicker.

The above image shows a .45 round (above left between the 3″ and 4″ mark on the ruler) after a head-on strike with concrete and steel. The other distorting of bullets occurred when striking various surfaces from a variety of angles—ricochet rounds.

Bullet or Cartridge? Are You Writing it Wrong?

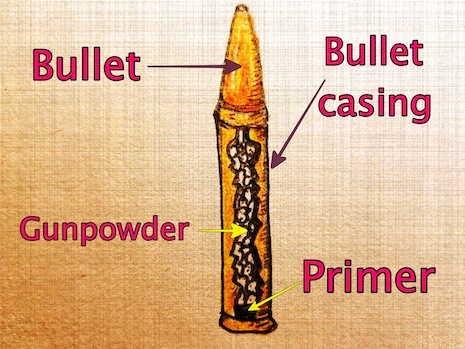

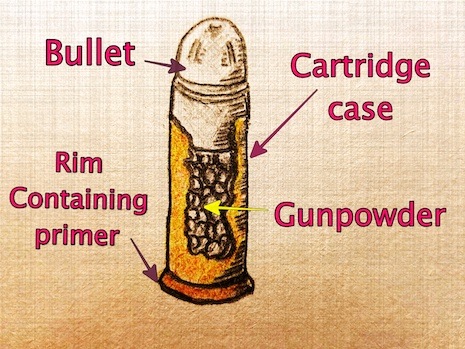

A bullet is the projectile portion of a cartridge, not the entire round.

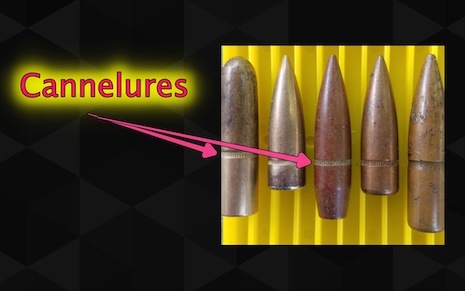

4 components of a cartridge are the casing, primer, powder, and bullet

Casing: The container, such as brass, steel, or copper (pistol and rifle ammunition). Shotgun shell casings are typically made of plastic.

Primer: The primer is an explosive material that ignites the gunpowder when struck by a firing pin. Primers are located either in the center of of the base of the casing (centerfire), or in the rim of the base (rimfire).

Powder: The powder used in modern ammunition is smokeless powder, an explosive consisting either of nitrocellulose alone (single-base), or double-base, a combination of nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin).

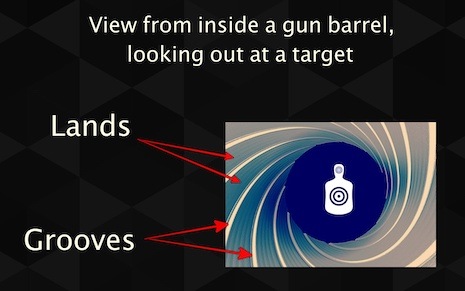

Bullet: The cylindrical and pointed projectile that is expelled from the gun barrel.

A round is a single cartridge – “The magazine holds 15 rounds.”

Hitting the hard solid surface head-on caused the .45 bullet to expand and fracture which creates the often larger exit wounds we see in shooting victims.

Many times, those bullet slivers break off inside the body causing further internal damage.

The size of an exit wound also depends on what the bullet hits inside the body. If the bullet only hits soft tissue the wound will be less traumatic. If it hits bone, expect much more damage. Easy rule of thumb—the larger the caliber (bullet size), the bigger the hole.

Bullets that hit something other than their intended target, such as a brick wall or metal lamp post, can break apart sending pieces of flying copper and lead fragments (shrapnel) into crowds of innocent bystanders. Those flying ricochet fragments are just as lethal as as any intact, full-sized bullet.

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Bullets don’t always stop people. I’ve seen shooting victims get up and run after they’ve been shot several times. And for goodness sake, people don’t fly twenty feet backward after they’ve been struck by a bullet. They just fall down and bleed. They may even moan a lot, or curse. That’s if they don’t get back up and start shooting again. Simply because a suspect has been shot once or twice does not mean his ability, or desire, to kill someone is over, and that, writers, is why police officers are taught to shoot until the threat is over.

The bank robber I shot and killed during a shootout fell after each of the five rounds hit him. But he also stood and began firing again after each of my bullets struck—one to the head and four to the center of his chest area. After the fifth round he stood and charged officers. Four of the five rounds caused fatal wounds. Yet, he still stood and ran toward officers. I and a sheriff’s captain tackled and cuffed him. In another instance, a man engaged in a gun battle with several officers. He was shot 33 times and still continued walking toward officers.

Always keep Sir Isaac Newton and his Third Law of Motion in mind when writing shooting scenes. The size of the force on the first object must equal the size of the force on the second object—force always comes in pairs.

Here’s Professor Dave to explain …

So, if your scene shows the shooting victim flying that twenty feet away from the person firing the rounds, the shooter would also fly twenty feet in the opposite direction. Ah, sounds silly, right? So toss this one in the trash can along with the use of cordite. No, no, and NO!