ASCLD – American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors.

AFIS – Automated Fingerprint Identification System. Palmprint storage and search capabilities are also in place.

ALPS – Automated Latent Print System.

ASCLD/LAB – American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Accreditation Board.

Acid Fuchsin – Reddish protein stain used to enhance bloody friction ridge detail of fingerprints.

Acid Yellow 7 – Fluorescent dye stain used to help visualize latent prints left in blood on nonporous surfaces.

Acid Yellow-7, Arrowhead Forensics

Acidified Hydrogen Peroxide – Solution used to develop friction ridge detail on cartridge casings by etching the surface of the casing not covered with sebaceous material (oils and/or fats).

Adactylia – Congenital absence of fingers and/or toes.

Adermatoglyphia – Extremely rare congenital absence of fingerprints.

Alanine – The most common amino acid found in proteins. Alanine is often

used to test latent print chemicals for an amino acid reaction.

Aluminum Chloride – A metal salt used to treat ninhydrin developed latent prints.

Amicus Brief – Legal document filed by someone not associated with a case but possibly has knowledge of a subject matter that may be of interest to the courts. The person submitting the brief is known as amici curiae.

Amicus Curiae – Latin for “friend of the court.”

Amido Black – Bluish-black stain used to enhance bloody fingerprint friction ridge detail.

Anhidrosis – Medical condition that reduces or prevents the body’s ability to sweat.

Benzidine – Once described as the best technique for developing bloody latent prints on nonporous items, Benzidine has been linked to cancers and is no longer used.

Bichromatic ™ – A multi-colored powder used to process an object for fingerprints.

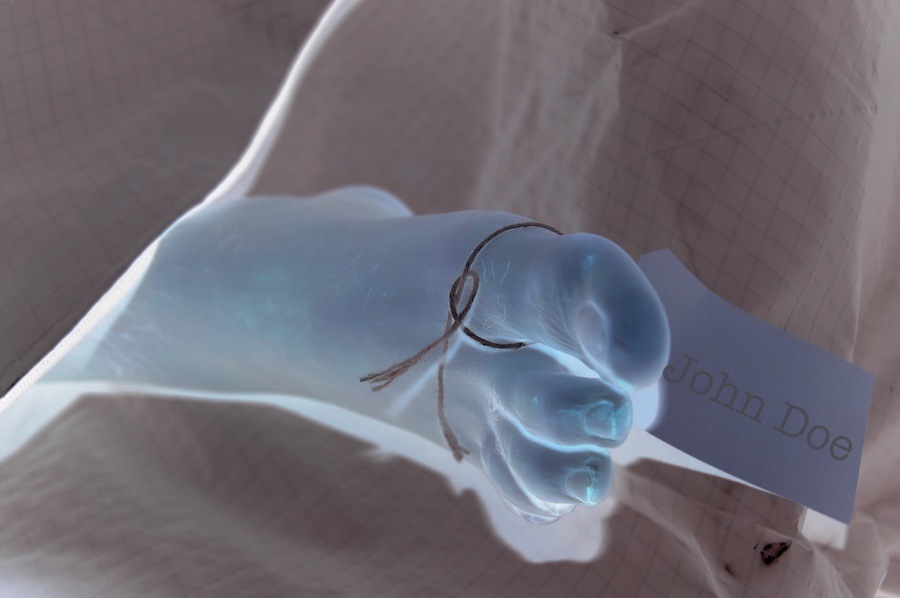

Boiling – Method used to re-hydrate the friction skin/fingerprints/footprints of a deceased person. To process the prints water is boiled and them removed from the heat. The hand of the deceased is submerged in the water for approximately five seconds. The skin is then dried and the fingers and/or palm is printed.

CJIS – Criminal Justice Information Services Division.

Calcar Area – The area located at the heel of the foot.

Cheiloscopy – The study of lip prints.

Clandestine – In secret.

Cluster Prints – More than one fingerprint grouped/clumped/positioned in the same spot of a surface.

Comparator – A split image projection screen used to view and compare fingerprints.

Core – Center of a fingerprint pattern.

Dactylography – The study of fingerprints as a method of identification.

De-gloving – The accidental/unintentional separation of the skin from the hands or feet. This “skin slippage” often occurs after a body has been submerged in water for a period od time.

Diff-Lift™ – Fingerprint lifting tape made especially for use on textured objects.

Dorsal – The backside of the hand.

Erroneous Exclusion – Disregarding evidence without a sound basis for doing so.

Exemplar – The known prints of a known individual.

FLS – Forensic Light Source. Includes all light sources used in forensic examinations.

FRE – Federal Rules of Evidence.

Fingerprint Society – Yes, it’s a thing. The Fingerprint Society was conceived in 1974 by Martin J. Leadbetter.

Genipin – A reagent used to develop friction ridge detail on porous items. The result is a dark blue image that can be seen without enhanced lighting.

Hallux – A person’s big toe.

Sir William James Herschel – The first European to recognize and utilize the value of fingerprints for identification purposes.

Histology – The study of the microscopic structure of animal or

plant tissues.

Hot Breath Technique – Breathing on a latent fingerprint either to help visualize the print or to add moisture back into an older latent print. Also known as Huffing.

Hyperhidrosis – Medical condition that increases sweating. Sometimes caused by certain medications, or heredity.

Hypohidrosis – Medical condition that decreases sweating. Sometimes caused by certain medications, or heredity or damage to the skin.

IAFIS – Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System. The FBI’s first

fully automated AFIS computer database.

Image Reversal – Occurs when the friction ridges in a latent print are reversed. Unintentional transferred prints could occur when using rubber lifters. It’s even happened when items are stacked on top of one another (stacks of evidence bags, for example), causing a print to transfer from one item to the next. The same is true with books. A print from one page could transfer to the next page (after the book is closed for a long time). These prints are mirror images and should be obvious to a trained examiner.

Latent Print – Print that is visible to the naked eye.

Liqui-drox – Fluorescent (yellow) solution used to enhance/develop fingerprint friction ridge detail on the adhesive and non-adhesive sides of dark colored tape.

Loupe – Small magnifying glass used to examine prints.

In those days there wasn’t a lot of consideration for sterility, and DNA hadn’t yet made its way on the “scene.”

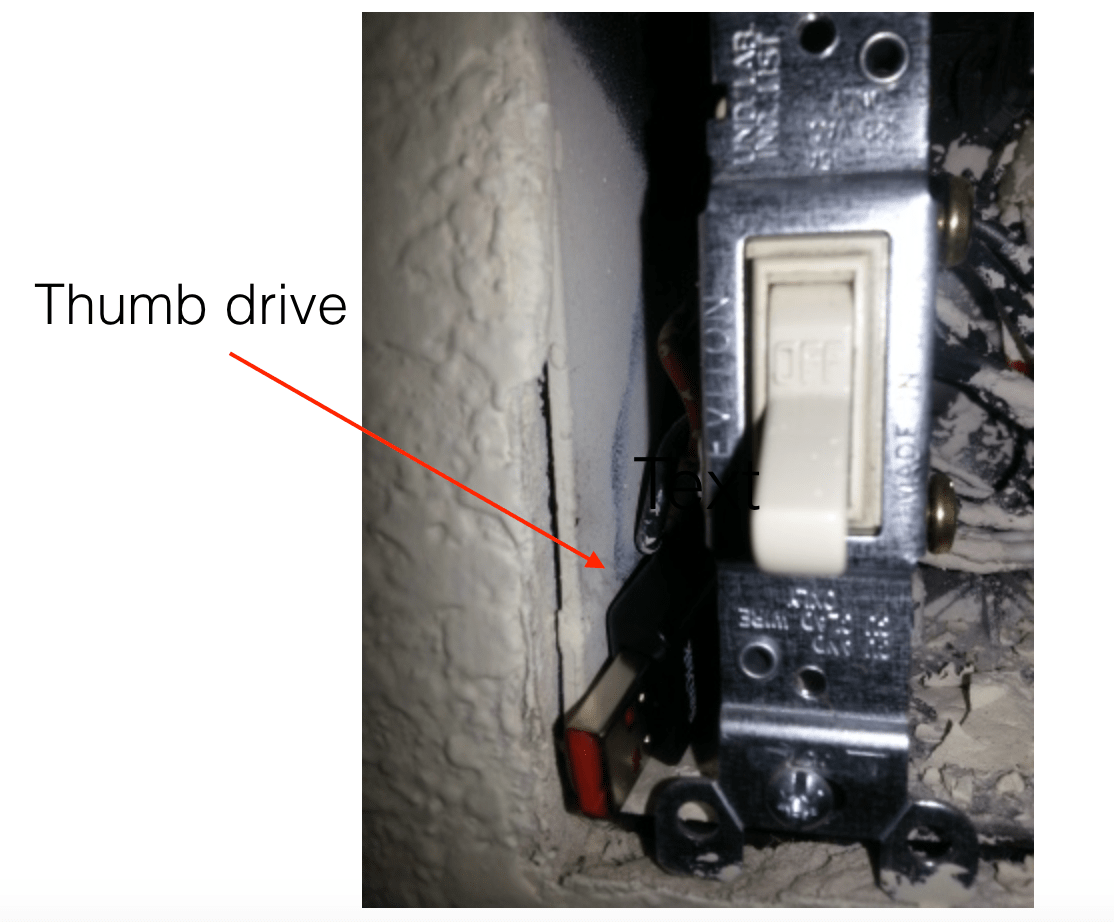

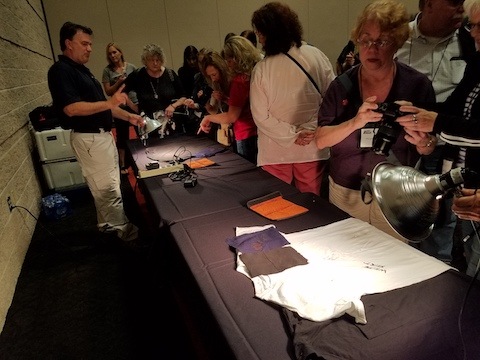

In those days there wasn’t a lot of consideration for sterility, and DNA hadn’t yet made its way on the “scene.” Items that could be cross-contaminated must be packaged separately. There’s a rule of thumb for other types of evidence, too, and here’s a handy list for the proper packaging of those items.

Items that could be cross-contaminated must be packaged separately. There’s a rule of thumb for other types of evidence, too, and here’s a handy list for the proper packaging of those items.

A quick DNA test of the blood found in the belly of the bug could quite easily reveal the name of the killer (if his information is in the system), and how cool would it be to bring in Mr. I. Done Kiltem and notice he has a fresh mosquito bite on his cheek? I know, right?

A quick DNA test of the blood found in the belly of the bug could quite easily reveal the name of the killer (if his information is in the system), and how cool would it be to bring in Mr. I. Done Kiltem and notice he has a fresh mosquito bite on his cheek? I know, right?