On The Job With Author Danny P. Smith

The Graveyard Shift is pleased to introduce a wonderful and talented author, Danny P. Smith. I first met Danny at a writers conference several years ago in California and my cop instincts told me he had what it takes to survive in a writer’s world. I was right.

Smith come from a long line of tough Chicago cops and I’m proud to call him my friend, especially since he survived a childhood as a cop’s kid. To me, that makes him just a little tougher than most people. My daughter would say that probably made him a little crazy. What can I say? He’s a writer. Welcome, Danny.

At first a high school English teacher, Daniel P. Smith left the world of education behind in 2004 to pursue the writing life. Less than five months removed from the classroom and all of 23 years old, Smith teamed with Chicago-based Lake Claremont Press to pen On the Job: Behind the Stars of the Chicago Police Department, a project inspired by his roots in a Chicago Police family. Already an award-winning, nationally published journalist, On the Job is Smith’s first book. A 2003 graduate of the University of Illinois at Chicago, Smith resides in Chicago’s western suburbs with his wife, Tina, and dog, Dublin. He lives in cyberspace at www.onthejob-smith.blogspot.com.

My mother always told me that my father’s downward spiral began when he found the Canzanerri boy. Though my father was on a self-destructive path, which included alcoholism and the eventual abandonment of his family, the Canzanerri case accelerated his demise. A Vietnam vet and Chicago cop, my father had encountered his share of tragedy and struggled at processing such events; the Canzanerri case, I’m told, was the beginning of the end.

In Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, a horde of the district’s cops assembled to begin their search for the missing infant.

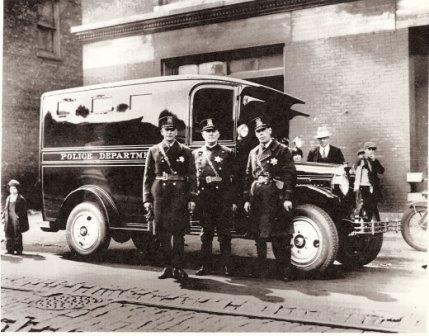

Chicago PD squad car

Searching one home, my father looked under the stairs to find a blanket. Opening the blanket, he discovered the Canzanerri boy—murdered and sliced. From then on, tells my mother, my father changed. He hit the bottle harder. He woke daily from nightmares. And he started talking feverishly about leaving the department so he could make quick cash elsewhere. Perhaps driven by his own mortality as well as the nightmares, my father left us. Though I’ve seen him in the 25 years since, I can’t say I’ve ever known my father or, to be truthful, wanted to know him. He was cold, unchanged, and guarded.

But what if the Canzanerri boy had never gone missing and my father didn’t make that discovery? Would my parents have remained married? Might I have grown up with a father? Doubtful—the selfish tendencies that sparked my parents’ separation existed long before the Canzanerri mystery and remain long after. Still, the case does show the ripple effects that police work sends throughout a cop’s life.

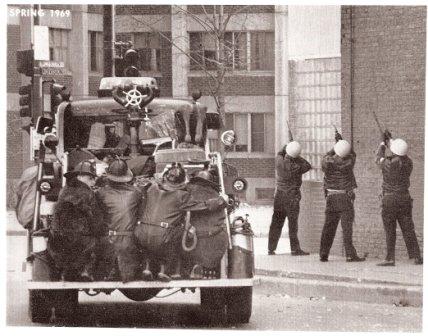

Chicago PD snipers

In the second half of 2004, I began penning my first book. Inspired by my roots in a Chicago Police Family, I wanted to explore the work-life juxtaposition Chicago’s officers face. For much of my life I couldn’t reconcile the public perception of officers—one that frequently labeled Chicago’s cops as lazy, corrupt, and prejudice—with what I knew from my home life, where four of six uncles were cops and my brother also wore the Chicago Police star. (With the exception of my father, in fact, all those men put their best effort forward each day for their families, communities, and city. To be certain, they each have their faults, but their passion for Chicago Police work and the city could not be mistaken.) I sought to tell human stories against the backdrop of the Chicago Police Department, seeking to examine the personalities behind the star (in Chicago it’s a star, not a badge or shield).

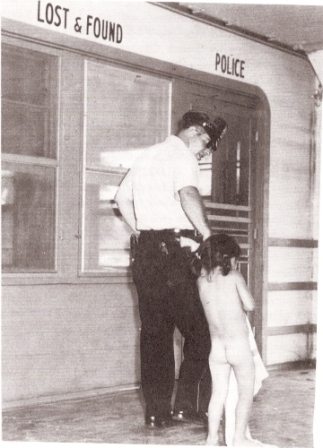

Chicago PD officer helping a lost child

Last month, On the Job: Behind the Stars of the Chicago Police Department arrived (https://www.lakeclaremont.com/prod_page.php?isbn=978-1-893121-12-6). Gratefully for this young writer, On the Job has earned glaring reviews for its candor and sincerity as it erases the Hollywood stereotypes as well as what we think we know of cops. The book is far less blood and guts and far more heart and soul. And the truth is that real police work requires more heart and soul than just about any profession in America.

It’s easy to be pulled into the silver screen lore or CSI’s drama, but real cops often snicker at Hollywood portrayals of their work. Dirty Harry shoots the bad guy and walks into the sunset, right? Well, it doesn’t happen that way, particularly for the cops who reflect on their work in the realm of human relations. Police work consumes the soul as much as the days. It’s work that alters one’s view of the world as well as one’s perception of life’s fellow travelers. As soon as officers take that oath, they sacrifice a piece of themselves—perhaps their trust or faith or relationships suffering from the job’s constant tension. It’s a helluva price to pay for a blue-collar civil service job. Any cop who says he or she’s the same as the day they entered the job is either: a.) lying or b.) never really been the PO-LICE. The job changes minds and souls and futures. It does not allow for stagnation.

So what tidbits might I be able to offer you, the aspiring crime writer who seeks stories based in truth and accuracy?

True, you’ll need to have your facts and jargon down; you’ll need to know the culture and organization of any law enforcement unit you discuss; and you’ll need to have the details of a given investigation in order. But above all, you’ll need to remember that any story, whether about cops or farmers or plumbers, is ultimately about people. And I’d make the argument with vigor and purpose that the cops’ stories, in particular, must adhere to this principle without fault because in the job maintains such an overwhelming impact on one’s life.

As a high school teacher, I would begin each school year by asking my students the following: Why do we read? They’d come up with a litany of answers that we’d jot on the blackboard—entertainment, knowledge, escape, etc. But in the end, don’t we really read for the same reason we watch reality TV? We read to see how people deal with shit, don’t we? How do people grieve and live and overcome adversity? How do people build relationships and find a place in society? How do people react to tragedy and triumph? How do people reconcile their actions?

In On the Job: Behind the Stars of the Chicago Police Department such is certainly the task I set out to accomplish: to tell human stories in which we, as readers, get a glimpse into how people deal with life’s diverse range of challenges and successes. Early reader response tells me I did my part. I sparked empathy for Chicago’s officers and an understanding of their lives by sharing stories anchored in sincerity and heart. I told stories about people.

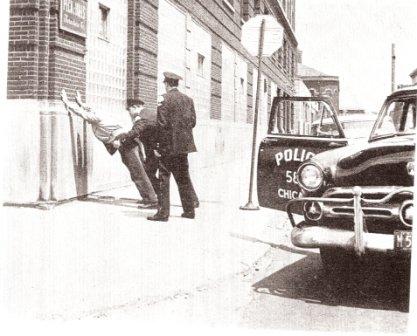

Chicago officers conduct a pat-down search

Now the challenge is how can you do the same and, at least for today, how can I help you move your own writing ambitions forward?

Melanie – Your story rings loud and clear. I’ve seen many like it over the years. Too many.

Danny – Thanks for taking the time out of your schedule to share a portion of your life with us. I think you’ve opened a few eyes and filled a few hearts with your insight and compassion. You’re always welcome here my friend.

As the day draws to a close in my Chicago home, much thanks to Lee Lofland for the invitation and to the many guests who welcomed me and engaged in some fascinating conversation. For west coasters as well as insomniacs, I’ll check back first thing in the morning and respond to any of the night’s postings.

It’s been an insightful and interesting day and I look forward to visiting The Graveyard Shift once again.

Onward,

Daniel P. Smith

Author, On the Job: Behind the Stars of the Chicago Police Department

smithwriting@gmail.com

http://www.onthejob-smith.blogspot.com

Melanie:

Sadly, your story is an all too common one. Much like your tale, I know my father became somebody my mother didn’t recognize and that’s what sparked their separation and divorce.

There is a distinction, however, I feel that’s important to make. We have to be careful in saying that the job alone creates cynicism, sarcasm, anger, closed-mindedness, etc. Much of what an officer sees sparks those feelings. But it was his internalization of those emotions that lead to his downfall–as well as the downfall of my father. How does one officer see much the same and live a life as a productive parent, spouse, and friend while another officer falls deep into the bottle or jaded thought.

In On the Job, I speak with an officer who feel into deep alcoholism after shooting a suspect. While others patted him on the back, he felt awful about what he did. To keep that public persona, he hit the bottle harder and harder. He showed up drunk to work countless times and eventually made the decision himself that he couldn’t do it anymore. He sought help, something too few officers do. In the end, his story is one of triumph. Sober for nearly two decades, he recently retired from the Chicago PD. He’s a shining example of how police work can spark one’s downfall and also reward one’s idealistic aims.

This discussion is absolutely fascinating. I was married to a cop for eleven years, and I watched my then-husband change over the years into a man I didn’t know. He became cynical, sarcastic, and angry. He internalized everything and did not have an outlet. He is now on his third marriage, lives in west Texas, and still works in law enforcement. I wouldn’t want to get in his way.

OMG…I remember hearing about that. Man, you guys are insane. A hoot to watch, but I’d be completely unable to do that. Kudos!!!!

Lee is a great guy.

Last year at CrimeBake we did a mock trial of Jack Reacher. Lee played Reacher and I played the part of the DEA agent. Michele Martinez was the prosecutor, Julia Spencer-Fleming was the defense attorney, Hank Phillipi Ryan was the news resporter, and Judge Ken Freeman played the part of the presiding judge. It was a hoot!

He’s our mentor for this year’s international thriller writer’s debut group. Now I can’t wait to meet him. What a compliment, Lee.

That was Jordan’s metaphor, but since it sounded so good I’ll take the credit.

I think anyone who reads Lee Child knows that fear is a driving force in his Reacher novels. Everyone, including the reader feels fear. Everyone, that is, except Jack Reacher. I don’t think Lee feels fear, either. He’s the kind of guy I’d like to have had as a detective partner.

Interesting, Lee, that you use a metaphor I use frequently in On the Job–ripple effect. The truth about law enforcement work, in particular, is that it remains a career that sends ripples throughout one’s life. That’s certainly the case I encountered as the son of a cop and it surely resonated with the many officers I interviewed in On the Job.

Author Lee Child said recently on a post that “it’s not about writing what you know, but writing what you fear.”

Your last post reminded me of that, Lee. Fear is primal and it resonates with all of us.

Jordan – The ripples across the water are the sensations and emotions that make us all believe what we read.

Lee–I think from this post–and other thoughts I’ve had recently–that I am systematically exorcising my own demons. I’ve chosen to do this through my cops and the victims in my debut series. They all represent an aspect like an out of body experience–a different perspective of how violence touches each of us–the ripple across the water.

Some reviewers have picked up on this and it’s gratifying to know they heard me–even if I didn’t realize it myself at the time I wrote it. Writing is definitely cathartic if we open out minds to it.

Danny – I can assure you that it’s quite easy to begin the journey on that dark path you’ve mentioned. I’m glad I was able to find a different route. It would have been far too easy to continue the downward spiral.

Danny –

You have such a fluid, authentic voice. You bring to life the harsh reality of being a cop – the side that the general public doesn’t see. I can’t wait to read this book. I’d love to review it for Pop Syndicate and tell readers more about it. Let me know if you are ever on virtual book tour. I’d love to feature you on our book blog.

Keep writing!

Angela

Wow, Lee, what a poignant comment.

As I noted in my initial post, my father didn’t have that positive outlet, but it’s something everybody–cop or dentist or postal worker–needs. Once he found that Canzanerri boy, the only outlet that he felt he could turn to was booze and the pursuit of selfish, unrealistic goals. He forgot about his family. He forgot about his work. And he’s traveled a dark path for much of the last two decades.

As for me, I’m going out for a run later this afternoon. After all, writers need outlets, too.

Jordan – One of my best friends – a fellow police officer – stopped a car for speeding one afternoon. When he approached the driver’s door he was shot twice. The driver was a wanted bank robber. We had no way of knowing this at the time because the computers were down for file purging and updating, something that happens regularly.

My partner in the detective division was shot three different times and stabbed once during his twenty plus years on the job.

I’ve been stabbed twice, cut once, and have been shot at a few times. I’ve given CPR to drug addicts who overdosed, and I’ve seen children killed by parents. I’ve also witnessed death in nearly every way imaginable, including the execution of one of the worst serial killers in our country.

I write to let these memories out. I can’t allow them to stay trapped inside. I feel fortunate to have writing as an outlet. Others aren’t so lucky and their lives reflect that misery.

Interesting story there, Joyce, and I think that’s far more common than the general public thinks: officers DO carry details and people and situations with them well into the future. Interestingly, most cases like that tend to involve children.

One of the officers I interviewed in On the Job was present at the 1968 Democratic National Convention and spent the following three decades of his career in one of Chicago’s most crime-ridden districts. Still, when I asked him about an event that sticks in his mind, he began telling the story of a young girl he found murdered–Miracle Moon was her name and she drowned in a bathtub. He has four young kids now and says that each time he puts his kids in the tub he thinks about Miracle. That’s what he carries with him.

Last year I wrote a blog post on Philadelphia’s Boy in the Box (http://workingstiffs.blogspot.com/2007/03/boy-in-box.html). It’s been fifty years since his body was found and the investigators who are still alive have never stopped looking for the boy’s killer. At one point, they even had his body exhumed and reburied in a grave that they paid for, and they still attend memorial services for him. So yes, they definitely carry the details with them for their entire lives.

Elena:

Have you ever heard of The Lovely Bones? A best-selling novel by Alice Sebold, The Lovely Bones gives us a subtle glimpse into the cop’s POV. There’s a detective in the book who carries around a photo of a still missing girl (that is, if my memory serves correctly). What a brilliant detail to toss in, don’t you think? You get to see what motivates that cop and get a short glimpse into his history.

I think your story told from the cop’s POV could be a fascinating one. Doing so would certainly allow you to create that distance while simultaneously telling a powerful story. Maybe look back into unsolved cases and see if you can find the names of retired officers who worked on different cases. See if you can revisit those officers. I can almost assure you they carry those details with them today and will talk with tremendous reflection and spirit on the case.

Jordan:

You say you could see the Lt. and others in the room being shaken by the video and therein lines the Blue Line that does separate us from them: every officer in that room knows it could’ve been him/her. That trooper was in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong dude. How was he to know that when he pulled over a guy for speeding or swerving or failing to make a proper signal before turning? He didn’t. It’s stories such as that which explain why the Blue Line exists and why so many officers remain steadfast that it be maintained.

How very amazing. I have tried many times to use various aspects of my violent childhood in writing, and I still can’t do it. I can’t get the distance, and hate going back into it.

However, I never thought of coming in from the cops POV and I’ve been playing around with it for the last several hours.

I do believe you’ve shown me a way to get there without tearing myself apart. What a lovely gift you have given me. Thank you.

In the sessions with our local police, they had us run practice scenarios where we had to walk up to a drunk or walk into a darkened room (to simulate the after hours of a store that had a burglar alarm going off). Many times, the police don’t have much to go on, except “an alarm is going off” and they have to assess the situation and anyone they come across quickly. Friend or foe? Armed or not? My adrenaline was pumping, I tell ya. I know we were all amateurs, but even with the proper training, judgment is still key.

And the same was the case when I did my ridealong at night. My suspicious nature kicked in and I found it hard to give the benefit of the doubt, not when walking up to a darkened vehicle at night. My cop had a death threat to file paper on and he had to try and find a terrorist suspect for an arrest. A strange night.

But it made me appreciate what law enforcement does to keep peace.

One night, we watched a video of a trooper that was killed by a drugged out motorist. To this day, I still hear the sounds in my head. He was shot 27 times with the last one in his eye. It was off camera, but the sounds were all there.

He was a new trooper. And many times the new ones are told out of training that there is potential liability if you pull your weapon and that they should be cautious about doing it. In this poor guy’s case, he kept calling the man “sir” until it was too late and the man pulled his rifle and began firing. A chilling image & sounds I won’t ever forget.

And while we were watching this video, the room got deathly quiet. I could tell my lieutenant and the other cops in the room had a hard time watching it. We all did. That night, I went home and rewrote a disturbing scene in my 2nd book, trying to do it justice–but of course, you can’t.

I’m looking forward to reading your book, Danny. I ordered it just now. Thanks for telling your story.

I think you’re right, Lee, it’s never the instinctual action that provokes the fear. It’s often the aftermath. I tell in On the Job the story of a cop involved in a shootout less than three weeks out of the academy. It wasn’t the shootout that got to him; it was the reflection of what could’ve been. I tell the stories of three different coppers who had to take a suspect’s life. All three battled with the effects of their action–one with booze, one with prayer/reconciliation, and another with the “I’m going home” philosophy.

And, Jordan, you’re dead on as well: killing is NOT a normal part of the job, but it IS a potential scenario one needs to understand that he/she could face as a PO. One reliable estimate has that less that 10 percent of Chicago’s officers have ever fired their gun. Rather amazing given the city’s criminal landscape and the amount of gun shots this city hosts each day (in On the Job, I give all the 911 calls for one 4-12 shift on the city’s west side–3 shots fired calls in one district, in one 8-hour shift). I think it’s simple to get caught up in the “Hollywood” aspect of police work, but the truth resides far from the camera’s lights.

I also try to convey in my books that killing is NOT a normal part of the job. Glad to hear you reinforce that here, Lee.

I also posted this blog to a few loops just now. I hope more people read this. Thanks to both of you.

Danny – Your story really hits home for me in many ways. I’ve read your book twice and can feel your emotions pouring from the pages. I’ll probably read it again, soon. It’s touching. Great job. I’m sure your dad is proud.

I’ve been on the door-kicking side of law-enforcement. There’s no fear going in – no time for it. It’s what cops are trained to do. But, I can assure you that once the danger subsides the realization of what could have been sets in. The emotional rollercoaster ride can be trying to say the least. You can almost feel your nerves stretched like rubber bands to their snapping points, and then suddenly released.

As many of you know, I was once in a shootout with a bank robber. I survived, he didn’t. That was a turning point in my career. The idea of killing someone was very, very difficult for me. It’s something I’ll never forget. The dead guy’s soul that lives in the edge of my thoughts won’t let me. So yes, Danny, there’s always a price to pay.

Thanks for joining us today. I hope you sell a trillion copies of your book.

Well said…and thanks.

Jordan:

Thanks for your energertic response.

I think you’re dead on in your assessment: police work is a way of life and that’s because it’s a job we take home with us, whether we want to or not. One of the most amazing lines I heard in all my interviews arrived from Chicago officer Dave Kumiega, who said, “Sometimes I wish I was a dentist.” Car jackings and armed robberies are not a daily event in the dentist’s life and so the dentist doesn’t think about them. For Dave, however, he changed his route home from the district every day; he double-checked that doors were locked; and he peeked in his rear-view mirror at stoplights.

As I said in an earlier post, I think there’s a tremendous amount of fascination with the psychological aspect of the job. Why does a traffic stop breed fear where busting down a door on a SWAT team does not rise to that same level?

While I admire the teamwork that exists on departments throughout the country, I do think that same “You can only understand me if you’ve been there, too” philosophy also serves an obstacle to maximizing their relationships with the public and, at times, one’s own family. Particularly in a big city, officers adopt an “us against them” mentality and the danger in that is that it puts all of us on different teams. Instead of one team working toward a unified city, we become sub-teams all working with our own agenda and looked with suspicion on those who aren’t on “our side.” So you’re right, that shared sense of duty can both unify and isolate. There’s always a price to pay, isn’t there?

Danny—Thanks so much for posting this story. I love absolutely everything you said here and it reinforces my treatment of law enforcement in my stories. My Brazil story dealt with police corruption, but it also showed a compelling story of one officer’s unflinching fight against it.

I took over 45 hours of presentations with my local police (including a day at the firing range) and have done the ride-alongs, but I came away with the idea that cops never get paid enough for what they do. And I’ve tried to understand the motivation to join the ranks, but I still don’t feel like I truly understand it. I think that’s why I keep writing about it. That job (more of a way of life) takes far more courage than I would ever have.

One of the officers that taught my CPA class had a small infant son–his first kid–yet he volunteered for tactical. (He was the number 2 guy thru the door.) And his mantra to get him through his confrontation with the meth dealer or hostage taker was saying over and over, “I’m the one that’s going home tonight”. I asked him why he volunteered for the extra duty, knowing he was exposing himself to more risk. And he said that he trusted his team and he considered it safer than a traffic stop.

From that story and countless others, I can see why officers form a tight bond with their team and other officers. No one can truly understand what it takes to serve unless they’ve been there. And over time, the sense of duty can strengthen that bond but also isolate a person.

And thanks for your candor on the relationship with your father. I’m currently writing a story (a subplot) that takes place in Chicago with a cop’s son. One case had put his father over an edge that he never came back from. And now the son is taking a journey, trying to understand his father thru the lives of the people his dad touched.

Your blog was exactly what I needed to hear today. Thanks again.

Jordan

Joyce:

I think you’re right about most officers’ mission to “protect and serve,” an idea that frequently sounds cliche but nevertheless rings true. One thing that compelled me to write On the Job was that I could not balance the public perception of Chicago’s officers with what I knew of officers from my personal life. With the exception of my father who faced those personal demons, my uncles and my brother were all men who went about putting their best foot forward each day for themselves, their families, their communities, and their city. Few officers do it for the money and, whether suburban or urban or rural, I think all cops recognize they might give a piece of themselves for the job–perhaps trustworthiness, family time, or idealistic notions. In many cases, that’s a helluva price to pay for a civil service job in which even the most rational citizens immediately think you’re a jerk when they hear the siren’s song (even when they know they were in the wrong).

Daniel, thanks so much for such a compelling post.

I work for a surburban PD (civilian), so the guys here don’t have to deal with many of the issues that a big city officer would have to deal with. Most of the guys here love their jobs and couldn’t imagine doing anything else. They truly want to “protect and serve.” I think that’s the case most places. They certainly aren’t doing it for the money!

Elena:

Thanks for your note and sharing a compelling story. Is there a book in there somewhere?

When I told people I was writing a book on the Chicago Police, the most common response was, “Oh, about all the corruption.” First, what a sad commentary on one of America’s most identifiable cities. But second, is that all that we believe Chicago’s cops are good for or, for that matter, law enforcement everywhere who are too often brandished as prejudiced, brutish, mechanical souls.

My book’s subtitle–“Behind the Stars of the Chicago Police Department”–has symbolic roots. In Chicago, officers wear a star (not a badge or a shield) on their left side, over their hearts. In getting “behind the stars,” I’m seeking to get to the heart. How do officers balance the work-life juxtaposition? Yes, officers are crime fighters. But they’re also human beings with human emotions. The same hands that arrest a criminal or collect evidence are the same hands that often go home and change diapers. How does one balance these dual roles? How does one affect the other and vice versa?

Think back to your story, might you imagine your story from the cops’ perspectives who went looking for you and then took you home. The officer who took you home, he was a father, right? That’s the point. His position as father influenced how he handled your case. He broke department code in taking you home, but encountered one of the cop world’s most interesting quandries: do I do what is honest or do I do what is moral?

While “The Graveyard Shift” certainly has its roots in police procedure and investigation, Lee and I thought it would be an interesting sidebar to discuss the psychological, sociological, and cultural issues that surround the copper’s life.

While any crime writer must establish the credibility that comes with detailing proper procedure and investigation, the pscyhological component plays just as critical a part. How do cops respond to some of the common situations they face? In what ways do they respond to political pressure (all departments are respondent to the politic in some way) or a life-chaging event (some pray at the graves of those they’ve killed while others urinate). Such is certainly what I hope to provide insight in given my countless interviews with Chicago’s officers, thereby escaping any stereotypes or Hollywood-driven perception.

I want to thank you for your book – it is long overdue.

In 1947 a Chicago cop saved if not my life, from serious injury involved in my having been kidnapped. And, then, rather than put my undersized and terrified self into juvenile detention, he broke regulations and took me home to his family to stay until the court decided what to do with me.

Looking back, he saved me not only from serious physical damage, but also, from the kindness of his heart mitigated the emotional damage.

A side of cops rarely shown.