Jerome and Crying Kids: Drugs, Not Money, are the Root of All Evil

During my earlier days a police detective, I spent a vast amount of time investigating drug crimes, typically involving large-scale narcotics activities. Most cases were those involving trafficking and sales, including pharmaceutical drugs and the forgery of prescriptions, etc., the manufacturing of methamphetamine and crack cocaine, and large marijuana grow operations.

I made it a part of my job to study not only the crime itself, but the habits and lifestyles of dealers and users, and this was to help me better understand the mindset of the players and their culture. This educational portion of my job provided an insight that I believed would serve two purposes.

The first was, of course, to help get the dealers off the the streets. The second was to help users rid themselves of their habits by entering into treatment programs and/or other means of finding the assistance and support they so desperately needed.

I tried to help dealers find suitable employment. The latter was also the case for the men and women I’d placed behind bars for their crimes. I offered to help secure meaningful employment after their release from jail or prison. Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. But my goal was to stop the problem at its source instead of waiting for the trouble to fester and then react to the trouble after the fact. And ounce of prevention, right?

But, sometimes nothing worked and the offenders went right back to their old ways, continuing the in-and-out cycle of breaking the law, going to jail, getting out with every intention of going straight, and then breaking the law again and again and again, and ….

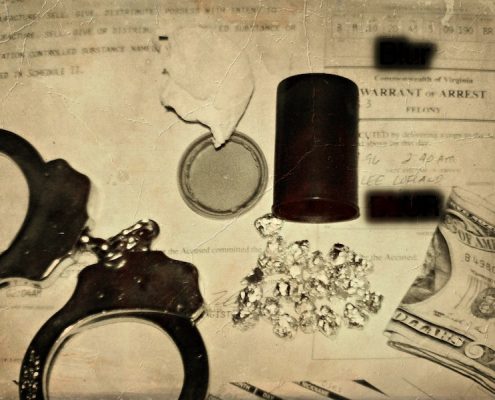

Felony arrest warrant served/executed by me after a stop and frisk led to guns, drugs, and cash.

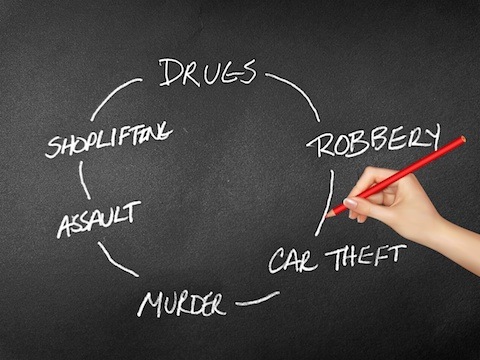

Later, while transitioning from narcotics investigations into other areas, I found that most criminal activity seemed to circle back to narcotics. And I found that even the informants with whom I’d dealt during the drug investigations were often in and around other criminal activity. The circle, in fact, was small. A never-ending and very tight loop.

Most crimes were connected by a single factor … drugs.

This circle, that never-ending and very tight loop I mentioned above is, in fact, quite small. And at the top of it was, of course, drugs.

The dealer sells to a user. The user shoplifts to purchase drugs. When he can’t steal he assaults someone and then steals their money (he robbed the victim). Then he steals a car to get away or to sell parts to get money to buy drugs. And sometimes they kill during robberies gone bad. Or drug dealers kill people who fail to pay, or they kill snitches or rival drug dealers.

I devoted a chapter about this issue in my book about police procedure.

Drugs, Not Money, Are the Root of All Evil

Police Procedure and Investigation

Drugs, Not Money, Are the Root of All Evil – Chapter 11 of Police Procedure and Investigation

Many homicides often involve the use and abuse illegal drugs. Robbery, rape, assaults, abduction and even suicide, well, you name it and a drug of some type, including alcohol, is often involved. Not in all cases, but I think it would be a safe assumption to say that in most instances of criminal activity, drugs and/or alcohol are an underlying factor in the crime that resulted in a suspect’s arrest.

Not only are drugs interwoven into the commission of the crime that landed an abuser behind bars, the abuse of those substances has a far broader reach than what the general public sees on its surface. For example, did you know:

- Children of parents who abuse substances of various types are three times more likely to be physically and/or mentally abused.

- Children of substance abusing parents are four times more likely to be neglected in favor of those substances, or a factor related to those abused substances.

- The National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported that during the period between the years 2002 to 2007, 8.3 million children under the age of 18 lived with at least one parent who was addicted to a drug of some type, or a parent who abused substances (nearly 7.5 million lived with a parent who was dependent on or abused alcohol. Just over 2 million lived with a parent who was dependent on or abused other drugs.

- In 2012, 31% of all children placed in foster care were removed from their homes due to parental alcohol or drug use/abuse.

- 10% of all newborns are exposed to prenatal substance abuse.

- Between the years 2011 and 2012, nearly 6% percent of pregnant women aged 15 to 44 were users/abusers of illicit drug.

- Young, pregnant teens—15- to 17-year-olds —reported the greatest substance use/abuse overall, topping 18%.

- Children who’ve been sexually abused are nearly 4 times more likely to develop drug dependency.

Since a whopping 2/3 of the people in treatment for drug abuse report being abused as children, how many incarcerated individuals have found themselves in their current situations with drugs or alcohol as a contributing factor?

Danger to Children

According to the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), children under the age of 18 who reside in homes where drug related crimes and/or other similar incidents occur are referred to as “drug endangered children,” or “DEC”.

These children (DEC) are at risk due to exposure to the possession, manufacturing, and sales of illicit drugs, including the non-medical use of pharmaceutical drugs. In many cases, the risks involve bodily harm and sexual and/or emotional abuse. They’re often neglected to the point where they’ve been forced to fend for themselves, even having to find their own food and ways to keep warm in the winter.

They’re victims of PTSD and their exposure to drugs and drug paraphernalia is constant. They’re witnesses to pornography and they often reside in squalor, and where violence of all types, include murder, is an everyday lifestyle. Weapons are easily accessible to anyone in the home, including small children.

Children growing up in these horrid circumstances are sometimes forced to participate in sexual activities in exchange for money and/or drugs, and it is often their own parents who force them to do so. Sadly, this includes even small children and infants.

Children living in drug environments often test positive for drugs due to accidental inhalation, needle sticks, and ingestion, and even secondhand smoke inhalation due to being in close proximity to drug users while they’re using.

Many kids whose parents engage in the manufacturing of methamphetamine are at risk of exposure to extremely toxic and other dangerous chemicals including highly combustible materials that could and have leveled homes in a flash.

As a means to help victims of drug crimes, The DEA offers assistance by way of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Victim Witness Assistance Program (DEA-VWAP).

The much-needed program provides immediate emergency treatment by locating and introducing child and adult victims to appropriate service agencies. Other services include, but are not limited to, counseling and medical care, immediate access to safe shelter, and transportation and relocation assistance, to name a few.

State crime victim compensation programs are also available, and are in every state in the country, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

Victims of most violent or personal crimes—assault, rape, child abuse, and domestic violence, as well as family members of murder victims—are eligible for compensation. Victims of property crimes such as theft and burglary are not eligible for compensation. These programs help victims by covering the expenses for medical care, mental health counseling, lost wages and funerals.

From the DEA:

Crime Victims’ Rights

Under Title 18, U.S.C., Section

3771(a), a crime victim has the following rights:

1. “The right to be reasonably protected from the accused.

2. The right to reasonable, accurate, and timely notice of any public court proceeding, or any parole proceeding, involving the crime or of any release or escape of the accused.

3. The right not to be excluded from any such public court proceedings, unless the court, after receiving clear and convincing evidence, deter- mines that testimony by the victim would be materially altered if the victim heard other testimony at that proceeding.

4. The right to be reasonably heard at any public proceeding in the district court involving release, plea, sentencing, or any parole proceeding.

5. The reasonable right to confer with the attorney for the Government in the case.

6. The right to full and timely restitution as provided in law.

7. The right to proceedings free from unreasonable delay.

8. The right to be treated with fairness and with respect for the victim’s dignity and privacy.”

The Sad Tale of My Good Friend, Jerome

Jerome, a professional thief and drug addict who was no stranger to judges, cops, and attorneys, sat on a well-worn wooden bench outside a courtroom door. His attire for the day … an orange jumpsuit, handcuffs, a waist and ankle chains, and white rubber shower shoes. The tile beneath his feet was scratched and dented and dull, the effects of years of footsteps and scuffling of nervous feet of offenders, like Jerome, who’d waited their turn to hear whether or not they’d spend a portion of their lives behind bars.

If those walls could talk

The wall behind Jerome was mint green in color and had a row of individual greasy head-shaped stains above each of the benches lining the hallway, stains left behind by the men and women who’d committed crimes ranging from petty theft to killing and butchering other humans.

Jerome was nervous and scared. He was also once a dear friend of mine.

Our bond began when we were teammates on our school football squad. We were the meanest and nastiest linebackers around and together we were practically unstoppable when it came to at least one of us penetrating the offensive line. In fact, it wasn’t unusual at all for an opposing team to go scoreless against us, and part of that success was due to Jerome’s and my (mostly Jerome) hard hits at the middle of the line, along with our regular sackings of quarterbacks.

Back in the day, Jerome was big and muscular and could run seemingly as fast as a frightened deer. He also carried a high GPA. The guy was smart, witty, and popular. He didn’t smoke, nor did he drink alcohol, and he was quite outspoken when it came to condemning drug use. He had hopes of getting out of the projects and attending the University of North Carolina, and possibly a career in the NFL. Drugs and alcohol were not a part of that picture.

In those days, our football days, my friend was a bit vain, though. He spent a lot of time grooming in front of mirrors, storefront windows, or any other reflective surface capable of returning his image. He carried a large Afro pick in his back pocket and frequently pulled it out to work on his hair, and he was forever mopping and rubbing and slopping gobs of lotion on his arms and face until his molasses-colored skin shone like new money.

His perfectly-aligned teeth gleamed like the white keys on a showroom Steinway. And, for a big, beefy and manly guy, he smelled a bit like lavender garnished with a hint of coconut.

There in the courthouse, though, Jerome appeared weak and sickly. He was rail thin and his complexion was muddy. The whites of his once bright eyes were the color of rotting lemons; their rims, and the edges of his nostrils, were damp, just on the edge of leaking trails of tears and mucus.

His hands shook and his teeth, the remaining ones, were spattered with black pits of rot and decay. His breath smelled like a week-old animal carcass. His fingernails were bitten to the quick and his hair was dry, uncombed, and had bits of lint and jail-blanket fuzz scattered throughout, and it was flat on one side like he’d been asleep for days without changing positions. He smelled like the combination of old sweat and the bottom of a dirty, wet ashtray.

With a few minutes to kill before my first case was called, I took a seat beside Jerome, with my gun side away from him, of course. I asked him why he continued to use a drug that was ruining his life and could eventually kill him.

His lips split into a faint grin and then he said, “Imagine the most intense orgasm you’ve ever had, then multiply it a thousand times. That’s how it feels just as the stuff starts winding it’s way through your system. Then it really starts to get good. So yeah, that’s why I do it.”

Heroin (r) south east asian (L) south west asian

He clasped his hands over his belly, stretched his gangly legs out in front of him, and he started talking, telling me about the first time he got high and about the last time he used, and he spoke about everything between. He told me about about the things he stole to support his habit and he told me about breaking into his own grandmother’s house to take a few of her most prized possessions, things he traded to his dealer in exchange for drugs.

Prostitution for Drugs

Jerome told me he performed oral sex on men out at the rest area beside the highway. They, the many, many nameless truckers and travelers, had given him ten dollars each time he entered one of the stalls to do the deed. He described the urine smell and how disgusted he was with himself when he felt the knees of his pants grow wet from contacting whatever fluid was on the tile floor at the time. But whatever it took to get the next high was what he’d do.

Once, a man asked him for anal sex. He was desperate, so he agreed. Jerome said he was to earn twenty-dollars for enduring that painful and humiliating experience, all the while knowing the people in nearby stalls could hear what was going on. He said he’d read the graffiti on the wall above the toilet as a means to take his mind off the obese man behind him. When it was over the man pulled up his pants and left Jerome in the stall, crying. The man didn’t pay.

Jerome told me that he wasn’t gay—despised having sex with men is what he said—, but he did it for the high, even though he often vomited afterward when recalling what he’d done. But the drug was more important. It was THE most important thing in his life.

Heroin Fentanyl pills

$1,000 per day habit

My high-school buddy’s habit cost him a thousand-dollars each day, seven days a week, unless he wasn’t able to produce the funds. Then he’d grow sick with the sickest feeling on earth. The hurt was deep, way down to his very core. Even his bones hurt. He’d sweat and he’d vomit and vomit and vomit and vomit until the pain in his gut felt like someone inside was using a hundred power drills and another hundred jackhammers to assault his brain and lungs and emotions. His heart slammed against his chest wall like a sledgehammer pounding railroad stakes into hard-packed Georgia clay.

Then he’d drop to his knees in another restroom, or steal another something that would help make it all go away until the next time. And he’d do it over and over and over again.

Hydrocodone

Jerome was lucky. He was caught by a deputy sheriff who was passing by a house and saw Jerome climbing out—feet first—from a bedroom window.

He was awaiting arraignment the day I saw him sitting on the bench outside the courtroom door. A dozen or so other jail inmates occupied the nearby seats.

Jerome asked if I would call his grandmother to tell her he said he was sorry for all he’d done, and that he was starting to feel better and was ready to seek help as soon as he was back on the outside. I told him I’d tell her. Actually, I went one step further and stopped by her house to tell her in person. When I arrived, she offered me a glass of iced tea and then we sat at her kitchen table where she settled in to hear about her beloved grandson, the happy little boy she’d called “Lil Jermy” since the day he was born.

I didn’t talk about the prostitution or that her grandson was a thief and robber and that he’d once stabbed a women so he could take the last three dollars she had to her name. Instead, I told her that he loved her and that he was truly sorry for the things he’d done. And I told her that I’d help him in any way I could.

She sat there listening with fat tears leaking from her old and tired eyes, following the convoluted trails of deep wrinkles until they spilled onto her floral housecoat and freshly ironed apron.

After I finished the last of the tea, down to the tinkling of ice cubes at the bottom of the Mason jar, I told her I needed to get back to work. We stood and she thanked me and gave me one of her sweet grandma hugs. She was trembling so I held her for a moment, allowing her to cry without having to face me. Then she stepped back and told me that she’d be praying for my safety. She asked me to tell Jerome that she loved him and that she forgave him for stealing her things and selling them for drug money.

I said I would and then stepped outside onto the old woman’s front porch. It was all I could do to hold back my own tears.

Yes, drugs are evil. They hurt and they kill. They ruin the lives of good people.

Now, I said Jerome was lucky, and I say this because going to jail prevented him from using the drug he grown to so desperately depend upon. His body ached for it, yes, but he beat the sickness and lived.

Unfortunately, many have died because of that same ache.

What a heartbreaking tale.