Police academy training can be extremely intense at times. And, in most training academies the major source of a recruit’s stress stems from knowing they must successfully complete the program to remain employed with their departments. Anything below a passing score could result in immediate unemployment status.

In some areas academy recruits attend on their own dime, hoping that earning a police academy certification will land them a job with a police department or sheriff’s office. Paying your own way to attend a police academy is a roll of the dice that’s similar to the football draft, where outstanding players receive contracts while non-drafted players sometimes wind up as high school coaches or teachers. Fail a police academy and you may find yourself swinging a nightstick in a shopping mall.

Tuition and Sponsorships

Public Safety Academy tuition costs at Guilford Technical Community College (GTCC), a former home of the Writers’ Police Academy, is approximately $1,200 ($4,300 for out of state tuition). In addition, there’s an extra fee of approximately $1,100.00 for uniforms, textbooks, and supplies. However, recruits have the opportunity to obtain a sponsorship from a N.C. law enforcement agency.

A sponsorship occurs when a department backs the recruit with an unofficial/unwritten intention of hiring the person once they’ve successfully completed the academy. No guarantees, though. Still, the college/academy will waive the tuition fee for department-sponsored recruits. But the recruits are required to pay the $1,100 uniform, books, and supply fees out of pocket.

*This system is in place in North Carolina and may not be an option in other states where recruits must already be employed by a law enforcement agency prior to attending a police academy.

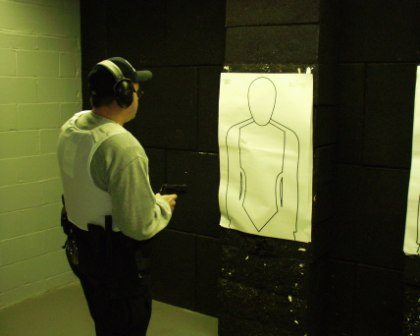

Police Academy Firearms Training

Before moving forward, I’d like to for say, thanks to author Donnell Bell and her response to a police firearms training question posted on the fabulous Crimescene Writer Q&A forum. In fact, the question is one I often receive from writers so I thought I’d expand a bit on her absolutely correct answer.

The question and Donnell’s answer is the basis for today’s article. If you’d like to learn more about Crimescene Writer and to take advantage of the numerous experts there—law enforcement (state. local, FBI), firefighters, medical examiners, attorneys, etc.—who answer questions from writers, please do click the link above and sign up. You’ll be glad you did, I guarantee.

Next, please keep in mind that standards vary from state to state, city to city, county to county, and department to department. However, all firearms training taught to police officers boils down to safety, when to shoot and why you should or shouldn’t, laws regarding using deadly force, and achieving a successful score on the firing range. And again, SAFETY! SAFETY! SAFETY!

As many of you know, I served as a police officer, a deputy sheriff, a corrections officer, and finally as a police detective. Firearms training for Virginia corrections officers is a bit different than that of a law enforcement officer, but I’ll save that information for another time.

Today, I thought it would be nice to offer the complete training objectives of firearms training in Virginia as set by the Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS). It is a minimum standard that is mandatory training for all officers. Academies may add to this standard but they may not cut corners by skipping steps.

Here are the minimum firearms training objectives. Please note that a successful score on the firing range is 70%. Officers there or in the other locations I’ve mentioned today are not required to shoot a 100% score.

Here’s a mystery for you to ponder. I won the award as top shooter in my academy class. My final score was 99%. There is a specific reason why I did not shoot 100% even though I could have done so, barring a sneeze or seizure at the time I pulled the trigger to fire the last round. Some of you may know why, but it is not something I’ll share in a public forum. Hmm …

Following the Virginia training objectives, for comparison, you’ll find those of Massachussetts, New Mexico, and Northern Virginia’s training academy. I’ve included the latter to illustrate that guidelines within the same state are different. The Northern Va. academy requires a higher range score than that of the state minimum.

This post is a bit lengthy so please bear with me and I believe you’ll find the information a bit useful and interesting. If not, well, I’ll see you tomorrow … 🙂

Off we go …

Police Academy Firearms Minimum Training Standards

Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS)

Firearms Training Objectives

1. Given a written exercise, identify nomenclature of weapons. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

2. Given a practical exercise, demonstrate prescribed procedure for cleaning weapon. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

Criteria: The trainee shall be tested on the following:

7.1.1. Identification of the correct terms to identify weapons and parts of weapons. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

7.1.2. Demonstration of prescribed procedure to prepare weapon for cleaning. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

7.1.2.1. Remove magazine or empty cylinder

7.1.2.2. Remove round from chamber

7.1.2.3. Double check weapon to make sure it is empty

7.1.3. Identification of weapon cleaning equipment. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

7.1.4. Demonstration of the use of weapon cleaning equipment. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

7.1.4.1. Field strip weapon

7.1.4.2. Clean components

7.1.4.3. Inspect for damage and imperfections

7.1.4.4. Lubricate

7.1.4.5. Reassemble

7.1.4.6. Safely test for proper function

Lesson Plan Guide: The lesson plan shall include the following:

1. Identification of the correct terms to identify weapons and parts of weapons. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

2. Demonstration of prescribed procedure to prepare weapon for cleaning. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

a. Remove magazine or empty cylinder

b. Remove round from chamber

c. Double check weapon to make sure it is empty

3. Identification of weapon cleaning equipment. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

4. Demonstration of the use of weapon cleaning equipment. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

a. Field strip weapon

b. Clean components

c. Inspect for damage and imperfections

d. Lubricate

e. Reassemble

f. Safely test for proper function

Performance Outcome 7.2.

Using proper hand grip and observation, draw department issued weapon from holster. (revolver or semi-automatic weapon)

Training Objectives Related to 7.2.

1. Given practical exercises, use a good and consistent combat grip with a safe and efficient draw from the holster following prescribed drawing techniques using the officer’s approved handgun and holster. (revolver or semi-automatic weapon)

Criteria: The trainee shall be tested on the following:

7.2.1. Draw and fire

7.2.2. Draw to a ready position

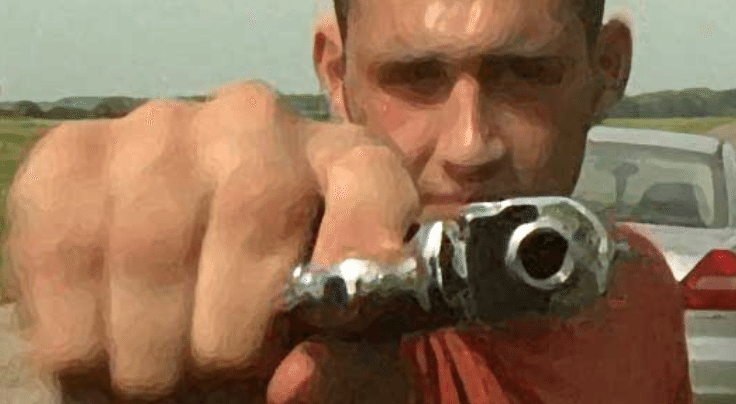

7.2.3. Draw to a “cover mode” simulating the covering of a suspect together with the issuance of the verbal order “Police – Don’t Move!”

7.2.4. Using standing, kneeling, and prone positions

7.2.5. Use of covering and concealment while maintaining visual contact with the threat

7.2.6. Reloading while concentrated on the threat and not the weapon

7.2.7. Clear handgun stoppages

7.2.8. Reholster weapon

Lesson Plan Guide: The lesson plan shall include the following:

1. Draw and fire

2. Draw to a ready position

3. Draw to a “cover mode” simulating the covering of a suspect together with the issuance of the verbal order “Police – Don’t Move!”

4. Using standing, kneeling and prone positions

5. Use of covering and concealment while maintaining visual contact with the threat

6. Reloading while concentrated on the threat and not the weapon

7. Clear handgun stoppages

8. Reholster weapon

Definitions:

a. Gripping: using sufficient strength to hold a weapon on a plane so that the projectile will travel on a line to the target

b. Lifting: having adequate strength to lift the weapon to eye level while maintaining safe control

c. Range of vision: should be such that a person can focus on one object (sights) and still see an image of the target

d. Strength: overall strength should be a minimum of being able to perform normal task without fatiguing quickly

e. Breathing: holding breath for a minimal time in order to complete the task of firing the weapon

f. Cover mode: finger outside the trigger guard until you are on target and have decided to fire

Performance Outcome 7.3.

Clear stoppage in semi-automatic pistols and revolvers. Demonstrate safe handling of weapons on the range and on and off duty.

Training Objectives Related to 7.3.

Given a practical exercise:

1. Demonstrate the techniques for clearing stoppages in pistols or revolvers.

2. Demonstrate safe handling of weapons on the range and how to do so on and off duty.

Criteria: The trainee shall be tested on the following:

7.3.1. Techniques for clearing stoppages:

7.3.1.1. Semi-automatic pistol

7.3.1.1.1. Failure to fire

7.3.1.1.2. Failure to feed

7.3.1.1.3. Failure to eject

7.3.1.1.4. Failure to extract

7.3.1.2. Revolver

7.3.1.2.1. When trigger is pulled and revolver does not fire

7.3.1.2.2. When trigger gets tight and cylinder will not turn

7.3.1.2.3. When there is a squib load

7.3.2. Demonstration of safe handling of weapons on the range and identification of safe handling of weapons on and off duty.

Lesson Plan Guide: The lesson plan shall include the following:

1. Techniques for clearing stoppages:

a. Semi-automatic pistol

1. Failure to fire

2. Failure to feed

3. Failure to eject

4. Failure to extract

b. Revolver

1. When trigger is pulled and revolver does not fire

2. When trigger gets tight and cylinder will not turn

3. When there is a Squib load

2. Demonstration of safe handling procedures of weapon while on the range and identification of safe handling procedures of weapon on and off duty.

Performance Outcome 7.4.

Fire a hand gun in various combat situations using issued equipment.

Training Objectives Related to 7.4.

1. Fire the officer’s issued/approved weapon during daytime/low light and/or night time combat range exercises using issued/approved loading device, issued/approved holster and flashlight with 70% accuracy on two of the approved courses of fire.

Criteria: The trainee shall be tested on the following:

7.4.1. Demonstrate dry firing and basic shooting principles.

7.4.2. Using proper marksmanship and reloading fundamentals, fire a minimum of 200 rounds with issued (or equal to this) ammunition in daylight conditions using issued/approved weapon prior to qualification.

7.4.3. Qualify on two of the below selected courses with approved targets under daylight conditions using issued (or equal to this) duty ammunition, weapon, duty belt and holster:

7.4.3.1. Virginia Modified Double Action Course for Semi-automatic Pistols and Revolvers, 60 rounds, 7, 15, 25 yards shooting. (See Appendix A shown below)

7.4.3.2. Virginia Modified Combat Course I, 60 rounds, 25, 15, 7 yards shooting (See Appendix B)

7.4.3.3. Virginia Modified Combat Course II, 60 rounds, 25, 15, 7, 5, 3 yards shooting (See Appendix C)

7.4.3.4. Virginia Qualification Course I, 50 rounds, 25 to 5 yards shooting (See Appendix D)

7.4.3.5. Virginia Qualification Course II, 60 rounds, 3 to 25 yards shooting (See Appendix E)

7.4.3.6. Virginia Tactical Qualification Course I, 50 rounds, 5 or 7, 25 yards shooting (See Appendix F)

7.4.3.7. Virginia Tactical Qualification Course II, 36 rounds, 3 to 25 yards shooting (See Appendix G)

7.4.3.8. Virginia Tactical Qualification Course III, 50 rounds, 1/3 to 25 yards shooting (See Appendix H)

7.4.3.9. Virginia Tactical Qualification Course IV, 60 rounds, 1/3 to 25 yards shooting (See Appendix I)

7.4.3.10. Virginia Tactical Qualification Course V, 50 rounds, 1/3 to 25 yards shooting (See Appendix J)

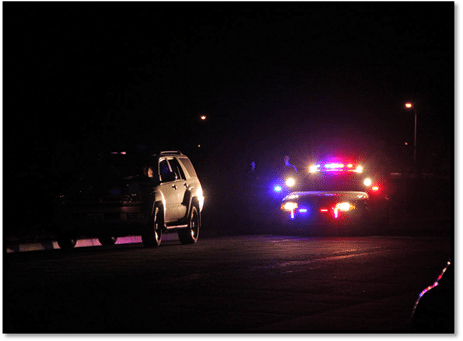

7.4.4. Fire a minimum of 25 rounds on a low light and/or a minimum of 25 rounds on a nighttime course for practice prior to qualification using the agency issued or approved handgun, duty holster and loading device.

7.4.4.1. Fire a minimum of 25 rounds on a low light and/or a minimum of 25 rounds on a nighttime qualification course with a 70% qualification score on each course.

7.4.4.2. Fire a minimum of 12 rounds with use of a flashlight in Appendix B or Appendix C above.

7.4.4.2.1. Identify the advantages and disadvantages of three methods of flashlight use with a weapon.

7.4.4.2.2. Identify the correct target threat by using flashlight techniques and weapon in hand.

7.4.4.3. Low light and nighttime practice and qualifications courses with time limitations and distances will be established by the school, agency, or academy board.

7.4.4.4. Fire from point shoulder positions, cover down positions and barricade positions.

7.4.4.5. Fire using strong and weak hand as appropriate:

7.4.4.5.1. Standing position

7.4.4.5.2. Kneeling position

7.4.4.5.3. Prone position

7.4.4.6. Reload the weapon with emphasis on utilizing tactical reloads where appropriate

7.4.4.7. Correct any weapon stoppages that may occur

7.4.5. Fire familiarization drills using a minimum of 50 rounds (10 per position) with issued (or equal to this) ammunition to include:

7.4.5.1. Moving forward and backward (officer and/or target).

7.4.5.2. Moving side to side (officer and/or target).

7.4.5.3. Use of cover and concealment.

7.4.5.4. Shove and shoot.

7.4.5.5. Seated straight/90 degrees to simulate shooting from a vehicle.

Performance Outcome 7.5.

Secure weapons while off duty. (revolvers, semi-automatic weapons)

Training Objectives Related to 7.5.

1. Given a written exercise, identify reasons for and methods for avoiding firearms accidents while off duty.

Criteria: The trainee shall be tested on the following:

7.5.1. Reasons for security

7.5.1.1. Prevent injury and unauthorized access

7.5.1.2. Minimize theft opportunity (separate ammunition from the weapons)

7.5.2. Methods for security

7.5.2.1. Lock box

7.5.2.1.1. Loaded

7.5.2.1.2. Unloaded

7.5.2.2. Trigger lock

7.5.2.2.1. Unloaded

7.5.2.3. Cable lock

7.5.2.3.1. Unloaded

7.5.2.4. Disassemble weapon

Lesson Plan Guide: The lesson plan shall include the following:

1. Reasons for security

a. Prevent injury and unauthorized access

b. Minimize theft opportunity (separate ammunition from the weapons)

2. Methods for security

a. Lock box

1. Loaded

2. Unloaded

b. Trigger lock

1. Unloaded

c. Cable lock

1. Unloaded

d. Disassemble weapon

Performance Outcome 7.6.

Carry a firearm when off duty. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

Training Objectives Related to 7.6.

1. Given a written exercise, identify the factors to consider when carrying a firearm while off duty. (revolver, semi-automatic weapon)

Criteria: The trainee shall be tested on the following:

7.6.1. Identification that an officer must comply with department policy relating to carrying a firearm while off duty and qualifying with the off duty firearm.

7.6.2. Identification of statutes that regulate the carrying of firearms while off duty.

7.6.3. Identification of the impact that alcohol consumption may have on judgment relating to use of firearms while off duty.

7.6.4. Identification of conditions that should be maintained while carrying a firearm off duty.

Lesson Plan Guide: The lesson plan shall include the following:

1. Identification that an officer must comply with department policy relating to carrying a firearm while off duty and qualifying with the off duty firearm.

2. Identification of statutes that regulate the carrying of firearms while off duty.

3. Identification of the impact that alcohol consumption may have on judgment relating to use of firearms while off duty.

4. Identification of conditions that should be maintained while carrying a firearm off duty

a. Concealed

b. Cecure (retaining device)

c. Accessible

d. Law enforcement identification with weapon

e. Jurisdiction

f. Training

5. Identification of response to being stopped by on-duty officer:

a. Upon being challenged, members will remain motionless unless given a positive directive otherwise.

b. Members will obey the commands of the challenging member, whether or not he/she is in uniform. This may entail submission to arrest.

c. Members will not attempt to produce identification unless and until so instructed.

d. If circumstances permit, members may verbally announce their identity and state the location of their badge and credentials.

e. Members should ask the challenger to repeat any directions or questions that are unclear and should never argue with challenger.

f. Challenged members will follow all instructions received until recognition is acknowledged.

Basic Firing Range Course for Academy Recruits

WEAPONS PERFORMANCE OUTCOMES

APPENDIX A – 60 rounds, 7, 15, 25 yards shooting.

VIRGINIA MODIFIED DOUBLE ACTION COURSE FOR SEMI-AUTOMATIC PISTOLS AND REVOLVERS

Targets- B-21, B-21X, B-27, Q

60 ROUNDS, 7 – 25 YARDS

Qualification Score: 70%

Each officer is restricted to the number of magazines carried on duty. Magazines shall be loaded to their full capacity. Range instructor shall determine when magazines will be changed.

PHASE 1 – 7 YARD LINE: With loaded magazine, on command fire 1 round in 2 seconds or fire 2 rounds in 3 seconds, make weapon safe, holster, repeat until 6 rounds have been fired.

1. On command draw and fire 2 rounds in 3 seconds, make weapon safe, holster, repeat until 6 rounds have been fired.

2. On command draw and fire 6 rounds strong hand and 6 rounds weak hand in 20 seconds for semi-auto and 30 seconds for revolver, make weapon safe and holster.

PHASE 2 -15 YARD LINE: Point Shoulder Position

1. On command draw and fire 1 round in 2 seconds or 2 rounds in 3 seconds, make weapon safe, holster, repeat until 6 rounds have been fired.

2. On command draw and fire 2 rounds in 3 seconds, holster and repeat until 6 rounds have been fired.

3. On command draw and fire 6 rounds in 12 seconds, make weapon safe and holster.

PHASE 3 – 25 YARD LINE: On command fire 6 rounds from prone, 6 rounds from kneeling and 6 rounds from standing until 18 rounds have been fired in 75 seconds for semi-auto, strong hand; for revolver,

90 seconds, strong hand. The order of position and use of cover/concealment and decocking is optional with the instructor.

SCORING – B21, B21X targets – use indicated K value with a maximum 300 points divided by 3 to obtain percent.

B27 target – 8,9,10,X rings = 5 points, 7 ring = 4 points, hits on silhouette = 3 points divided by 3 to obtain percent.

Q target – 5 points inside the bottle, 3 points outside the bottle on the target. Divide by 3 to obtain percent.

Louisiana Peace Officer Standards and Training Council (POST)

Basic Firearms Qualification:

- On a 25-yard range, equipped with POST approved P-1 targets, the student, given a pistol or revolver, holster and 240 rounds of ammunition, will fire the POST firearms qualification course at least four times. Scores must be averaged and the student must:

- Fire all courses in the required stage time;

- Use the correct body position for each course of fire;

- Fire the entire course using double action only, except in case of single action only semi-automatic pistols;

- Fire no more than the specified number of rounds per stage;

- Fire each course at a distance not appreciably lesser nor greater than that specified;

- Achieve an average score of not less than 96 out of a possible 120, which is 80% or above;

- Have all targets graded and final score computed by a POST-certified firearms instructor.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Municipal Police Training Committee

Annual Qualifications:

-

-

- Each officer shall successfully complete the MPTC Basic Qualification Course for each weapon at least once per year with:

- A minimum score of 80% and

- 100% round accountability. (See below for illustration of MPTC target.)

- While duty ammunition is not required for the qualification course, the caliber used forqualification shall be identical to that used for duty ammunition.

- The target used for qualification shall be the standard MPTC-approved target. (See belowfor approved targets.)

- The number of rounds needed for each weapon system is as follows:

Semiautomatic pistols = 50

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Northern Virginia Criminal Justice Training Academy

Performance-based objectives for Firearms Training and Driver Training are tested in the classroom and at the firearms and driver training ranges, and include both written examination questions and practical performance based testing. Recruits are required to score a minimum of 70% in each component. If a recruit fails to meet minimum standards after two attempts, the recruit will be scheduled for re-training at a later time. The recruit will receive remedial training and will be given up to two additional attempts to meet minimum standards.

New Mexico Public Safety and Law Enforcement

Qualification course: Day (50 round course) – A minimum score of 80% is required.

- Qualification course: Night (25 round course) – A minimum score of 80% is required. Low-light conditions would include parking lights from vehicles, naturally existing light, or other light that is just enough to identify a threat.

Finally, officers are required to maintain their shooting skills and must re-qualify annually.

Many officers enjoy shooting and do so regularly at firing ranges. Some departments provide ammunition for extra training, if their budget allows. If not, officers fund their own practice time.

It’s not unusual to see officers reload ammunition at home on their own time. Doing so is for target practice and results in a substantial monetary savings. However, only department issued ammunition may be carried while on duty and in off-duty weapons.

Since misidentification is the single greatest cause of wrongful convictions in the U.S., it is paramount to develop better discrimination accuracy when it comes to police lineups.

Since misidentification is the single greatest cause of wrongful convictions in the U.S., it is paramount to develop better discrimination accuracy when it comes to police lineups.

crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,500 articles and 69 books, including The Forensic Science of CSI, The Forensic Psychology of Criminal Minds, How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer, she was co-executive producer for the Wolf Entertainment/A&E documentary based on the years she spent talking with Rader. Dr. Ramsland consults on death investigations, pens a blog for Psychology Today, and is writing a fiction series based on a female forensic psychologist.

crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,500 articles and 69 books, including The Forensic Science of CSI, The Forensic Psychology of Criminal Minds, How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer, she was co-executive producer for the Wolf Entertainment/A&E documentary based on the years she spent talking with Rader. Dr. Ramsland consults on death investigations, pens a blog for Psychology Today, and is writing a fiction series based on a female forensic psychologist.

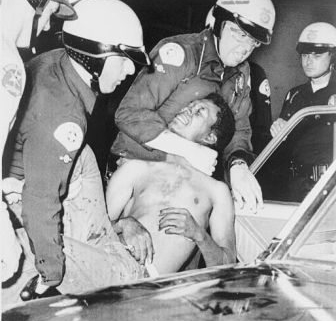

The object is always to gain control and cuff the suspect’s hands behind the back, with everyone involved remaining injury free, if possible. Again, though, when a suspect resists arrest officers must do what it takes to bring the situation to a quick resolution. The longer it goes on the more chance of injury.

The object is always to gain control and cuff the suspect’s hands behind the back, with everyone involved remaining injury free, if possible. Again, though, when a suspect resists arrest officers must do what it takes to bring the situation to a quick resolution. The longer it goes on the more chance of injury. I’m one of the early members of a defensive tactics federation. I have a strong background in

I’m one of the early members of a defensive tactics federation. I have a strong background in  But nothing seemed to work. He simply didn’t feel pressure applied to his joints and nerves. Even with several grown men trying to restrain him he continued to struggle and resist.

But nothing seemed to work. He simply didn’t feel pressure applied to his joints and nerves. Even with several grown men trying to restrain him he continued to struggle and resist.