Writers’ Police Academy Online is officially open, with a brand new June 25, 2022 class, new website, new design, new server, and exciting new, user-friendly live/online and on-demand courses currently in development. Class formats are video, audio, and/or text, or a combination of one or more. Details about the June class are below.

In the meantime, here are a few tidbits of information.

Why do law enforcement officers train by repetition – over and over again?

Each time an officer draws their weapon they perform a series of movements—place hand on the pistol, grip the pistol, release retention devices that prevent someone from taking the officer’s sidearm, remove pistol from holster, aim the gun toward the threat, insert finger into trigger guard, place finger on trigger, and finally, fire the gun.

Because officers train repetively, performing those same actions at the firing range, over and over again, the brain builds heavy-duty motor neural conduits

At the same time, myelin, a fatty substance, forms a layer of insulation that surrounds nerve cell axons. Myelin also escalates the rate at which electrical impulses move along the axon

As a result of repetitive firearms training, shooters build a high- speed connection that provides the ability to perform the “grip, release, aim, shoot” sequence without having to direct thought resources toward the details of the movement.

Instead of losing precious fractions of a second to analyzing “what’s step one, two, three, and four” the officer reacts instinctively to a threat.

WPA Scholarships Available for Writers’ Organizations

As a way of giving back to the many writers and writers organizations within the crime-writing community who’ve supported the Writers’ Police Academy over the years, we’re pleased to offer your organization a free registration/scholarship to the 2022 Writers’ Police Academy.

For details, please ask a board member of your group to contact Lee Lofland at lofland32@msn.com. The process is simple, request a scholarship and it will be yours to award to a member of your organization.

*Scholarship covers registration fee only. Hotel, travel, and banquet are not included.

Interactive 3D Police Lineups Improve Witness Accuracy

The capability of eyewitnesses to correctly recognize a guilty suspect from someone who’s totally innocent of a crime is known as discrimination accuracy.

Since misidentification is the single greatest cause of wrongful convictions in the U.S., it is paramount to develop better discrimination accuracy when it comes to police lineups.

Since misidentification is the single greatest cause of wrongful convictions in the U.S., it is paramount to develop better discrimination accuracy when it comes to police lineups.

Researchers at the University of Birmingham’s School of Psychology developed new interactive police lineup software that allows witnesses to view lineup faces in 3D. Using the program, witnesses can rotate and maneuver the faces of potential suspects to various angles that most likely correspond to the orientation of the face they remember from the crime scene.

During the experimental study where over 3,000 test witnesses observed a video of a crime in progress, results were astounding. Without a doubt, accuracy improved significantly when the witnesses viewed the lineup from the same angle at which they had seen the offender commit the crime. The results were better still when witnesses rotated the lineup faces to match the angle of the culprit’s face in relation to how they saw it while the crime was in progress.

15 Survival Tips for Real and Fictional Officers

- Remember these three words. You will survive! Never give up no matter how many times you’ve been shot, stabbed, or battered.

- Carry a good, well-maintained weapon. You can’t win a gun fight if your weapon won’t fire.

- Carry plenty of ammunition. There’s no such thing as having too many bullets.

- Treat every situation as a potential ambush. You never know when or where it could happen. This is why cops don’t like to sit with their backs to a door.

- Practice shooting skills in every possible situation—at night, lying down, with your weak hand, etc.

- Wear your body armor.

- Always expect the unexpected.

- Everyone is a potential threat until it’s proven they’re not. Bad people can have attractive faces and warm smiles and say nice things, but all that can change in the blink of an eye.

- Know when to retreat.

- Stay in shape! Eat healthy. Exercise.

- Train, train, and train.

- Use common sense.

- Make no judgements based on a person’s lifestyle, personality, politics, race, or religion. Treat everyone fairly and equally. However, remain alert and cautious at all times.

- Talk to people. Get to know them. Let them get to know you. After all, it’s often a bit tougher to hurt an officer they know and trust.

- Talk to people. Get to know them. Let them get to know you. After all, it’s often a bit tougher to hurt an officer they know and trust.

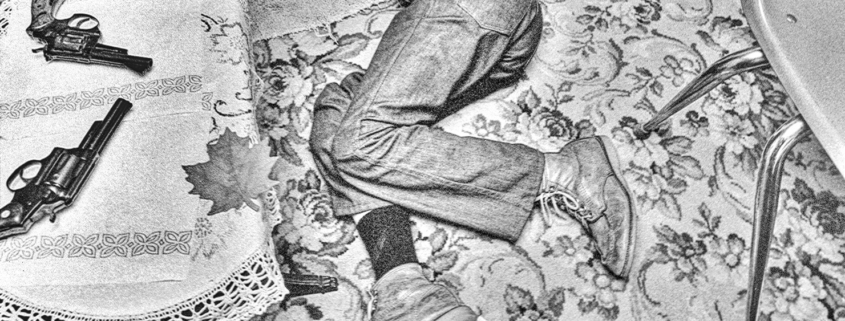

Presented by Writers’ Police Academy Online – “Behavioral Clues at Crime Scenes”

June 26, 2022

11:00 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. EST

Registration is OPEN for this fascinating live, online seminar taught by Dr. Katherine Ramsland. Session covers staging, profiling, character development, and more!

Sign up today at writerspoliceacademy.online

While you’re there, please take a moment to sign up for the latest updates, news, tips, tactics, and announcements of upcoming courses and classes.

About Dr. Katherine Ramsland

Dr. Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University in Pennsylvania, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200  crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,500 articles and 69 books, including The Forensic Science of CSI, The Forensic Psychology of Criminal Minds, How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer, she was co-executive producer for the Wolf Entertainment/A&E documentary based on the years she spent talking with Rader. Dr. Ramsland consults on death investigations, pens a blog for Psychology Today, and is writing a fiction series based on a female forensic psychologist.

crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,500 articles and 69 books, including The Forensic Science of CSI, The Forensic Psychology of Criminal Minds, How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer, she was co-executive producer for the Wolf Entertainment/A&E documentary based on the years she spent talking with Rader. Dr. Ramsland consults on death investigations, pens a blog for Psychology Today, and is writing a fiction series based on a female forensic psychologist.

In addition to the Writers’ Police Academy Online website moving to a new server, The Graveyard Shift is officially and finally up and running on the same server. Its new look is underway. The Writers’ Police

Academy is next to make the move and to receive an overhaul.

By the way, there’s still time to sign up for the 2022 Writers’ Police Academy!

Click here to view 2022 WPA hands-on sessions

If you’ve already registered please reserve your hotel rooms asap!

Reserve Your Room

Hilton Appleton Hotel Paper Valley

333 W College Ave, Appleton, Wi. 54911 – Phone: 920-733-8000

When calling, request reservations for the Writers Police Academy Block or, if reserving online, select dates of stay and enter group code 0622WRPA.

Writers’ Police Academy Merch

Writers’ Police Academy merchandise is available through our Zazzle store, including the 2022 t-shirts in a variety of colors.

Click here to view the selections.

Together we can better the world of crime fiction, one scene at a time.

Of course, you and your friend must attend the Writers’ Police Academy event in June to receive the rebate and free seminar registration. There is no limit as to how many rebates you may receive. If you refer ten friends and they each attend the WPA, well, you’ll receive $50 for each one. Twenty friends equal a rebate of $1,000! And so on.

Of course, you and your friend must attend the Writers’ Police Academy event in June to receive the rebate and free seminar registration. There is no limit as to how many rebates you may receive. If you refer ten friends and they each attend the WPA, well, you’ll receive $50 for each one. Twenty friends equal a rebate of $1,000! And so on. Register to attend at the 2022 Writers’ Police Academy at

Register to attend at the 2022 Writers’ Police Academy at

Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200 crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,000 articles and 68 books, including How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and The Mind of a Murderer, she spent five years working with Dennis Rader on his autobiography, Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer. Dr. Ramsland currently pens the “Shadow-boxing” blog at Psychology Today and teaches seminars to law enforcement.

Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200 crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,000 articles and 68 books, including How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and The Mind of a Murderer, she spent five years working with Dennis Rader on his autobiography, Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer. Dr. Ramsland currently pens the “Shadow-boxing” blog at Psychology Today and teaches seminars to law enforcement.

Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200 crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,000 articles and 68 books, including How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and The Mind of a Murderer, she spent five years working with Dennis Rader on his autobiography, Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer. Dr. Ramsland currently pens the “Shadow-boxing” blog at Psychology Today and teaches seminars to law enforcement.

Katherine Ramsland teaches forensic psychology at DeSales University, where she is the Assistant Provost. She has appeared on more than 200 crime documentaries and magazine shows, is an executive producer of Murder House Flip, and has consulted for CSI, Bones, and The Alienist. The author of more than 1,000 articles and 68 books, including How to Catch a Killer, The Psychology of Death Investigations, and The Mind of a Murderer, she spent five years working with Dennis Rader on his autobiography, Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, The BTK Killer. Dr. Ramsland currently pens the “Shadow-boxing” blog at Psychology Today and teaches seminars to law enforcement.