The writer, a lovely woman who writes as Esther Neveredits and who shares her office with seven cats of various sizes and personalities, opened the first chapter of her first book with the following passage.

“Detective Barney Catchemall followed the cop killer, a man named Folsom Blue, across seven states and forty-eight jurisdictions, to a house in Coolyville, California where he shot Blue in the arm with a single round fired from his department-issued semi-automatic revolver. He bandaged his prisoner’s wound (just a nick) and then brought him back to the city where the homicide took place and where he’ll stand trial before the Grand Jury on a charge of Homicide 1.

He’d been tried for the Homicide 1 charge once before but was found not guilty and set free with a clean record. However, the vindictive DA decided to try him again, hoping for a more suitable outcome, a conviction, which was practically guaranteed the second time around since the hardworking prosecutor personally handpicked the jury members … twelve badge bunnies. And, as soon as the paperwork was complete, he had plans to seize Blue’s oceanfront condo and his yacht. It was a good day. A good day indeed.”

So, did Ms. Neveredits have her facts straight? Yes? No?

Fortunately, and unlike Esther (bless her heart), most writers are pretty savvy when it comes to writing about cops and criminals and everything in between. And those who have questions … well, they typically ask an expert to help with the details. Or, they attend the Writers’ Police Academy where they’ll receive actual police training—driving, shooting, door-kicking, crime scene investigation, classes on the law and courtroom procedure, and so much more, and it’s all designed for writers.

But let’s return to Esther’s paragraph. What did she get wrong? The better question is how many things did she get wrong and in so few words?

- Is there an official charge of Homicide I?

- Are police officers permitted to cross jurisdictional boundaries, shoot a suspect, and then bring them back to stand charges?

- Do Grand Juries try criminal cases?

- Can a defendant be tried twice for the same crime?

- Can a prosecutor continue to bring charges against someone over and over again until they get the results they seek—a conviction?

- Semi-auto revolver? Is there such thing as a semi-auto revolver?

- What the heck is a badge bunny?

Okay, let’s dive right in.

Just say no to “Homicide 1”

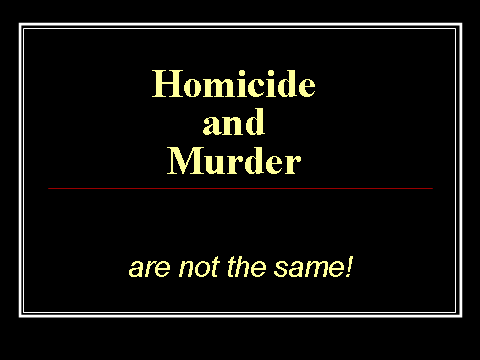

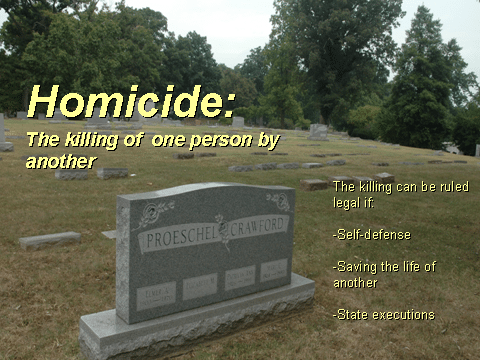

It is Murder that’s the unlawful killing of another person. The crime is usually deliberate or committed during an act that showed total disregard for the safety of others.

“I understand that murder is a crime,” you say, but … what’s the difference between murder and homicide? Don’t they share the same meaning? Is there a difference?

Yes, of course there’s a distinction between the two, and the things that set them apart are extremely important.

Again, murder is the unlawful killing of a person, especially with malice aforethought. The definition of homicide encompasses ALL killings of human beings by other humans. And certain homicides are absolutely legal.

By the way, animals (horses, dogs, pigs, cows, chickens, etc.), do not fall into the category of “all killings of human beings by other humans.” Therefore, there is no charge of murder for killing an animal. There are other laws that apply in those instances, but not, “Farmer Brown received the death penalty for murdering Clucky, his prized rooster.”

Anyway, yes, some homicides are indeed, L.E.G.A.L., legal.

Another term/crime you should know is felony murder. Some of you attended a popular and detailed workshop about this very topic at the Writers’ Police Academy.

To get everyone’s attention, a bank robber fires his weapon at the ceiling. A stray bullet hits a customer and she dies as a result of her injury. The robber has committed felony murder, a killing, however unintentional, that occurred during the commission of a felony. The shooter’s accomplices could also be charged with the murder even if they were not in possession of a weapon or took no part in the death of the victim.

Also, Manslaughter – Even though a victim dies as a result of an act committed by someone else, the death occurred without evil intent.

While attending a mind-numbing car race where drivers made loop after loop after loop around an oval dirt track, a quite intoxicated and shirtless Ronnie Redneck got into a rather heated argument with his best buddy, Donnie Weakguy.

Donnie Weakguy

During the exchange of words, Weakguy begins yelling obscenities and with the delivery of each four-letter word he jabbed a bony index finger into Redneck’s chest. Redneck , a man of little patience, took offense at the finger-poking and used both hands to shove Weakguy out of his personal space. Well, Weakguy, who was known countywide for his two left feet, tripped over his unconscious and extremely intoxicated girlfriend, Rita Sue Jenkins-Ledbetter, and hit his head on a nearby case of Budweiser. He immediately lost consciousness and, unfortunately, died on the way to the hospital as a result of bleeding inside the skull. Weakguy’s death was not intentional, but Ronnie Redneck finds himself facing manslaughter charges.

To address Ms. Neveredit’s additional missteps:

Jurisdiction – A law enforcement agency’s geographical area where they have the power and authority to enforce the law. The location is typically the area where the officer is employed and sworn to enforce the law. A city officer’s jurisdictional boundary is within the city limits (In most areas tthere is small allowance that extends beyond the city limits where officers are legally permitted to make an arrest.

Sheriffs and their deputies have authority in the county and any town or city within those boundaries, state police—anywhere in the state, federal agents—anywhere within the U.S. and its territories. To learn more about the exceptions please click over to my article titled Jurisdictional Boundaries: Step Across This Line, I Dare You.

Grand Jury – A panel of citizens selected to decide whether or not probable cause exists to charge a defendant with a crime. The Grand Jury hears only the prosecution’s side of the story. The defense is not allowed to present any evidence. In fact, the defense is not allowed to hear the testimony offered by the prosecution.

A Grand Jury does NOT try cases

Grand Jury members meet in secret, not in open courtrooms. Now you know why …

Asset Forfeiture – The government is allowed to seize property used in the commission of a crime. Many police departments benefit from the forfeiture of items such as, cash, cars, homes, boats, airplanes, and weapons. These items may be sold at auction, or used by the police.

For example, drug dealers use a 2010 Mercedes when making their deliveries. Police stop the car and arrest the occupants for distribution of heroin. Officers of a joint task force seize the car and subsequently fill out the proper asset-forfeiture paperwork. The vehicle is later forfeited (by the court) to the police department’s drug task force. They, in turn, assign the vehicle to their drug task force where officers use it as an undercover car. Other assets (again the items must be fruits of the illegal activity) are also seized and sold and the proceeds are divided among the agencies who participated in the bust and prosecution—prosecutor’s office, local police departments with officers assigned to the task force, etc.

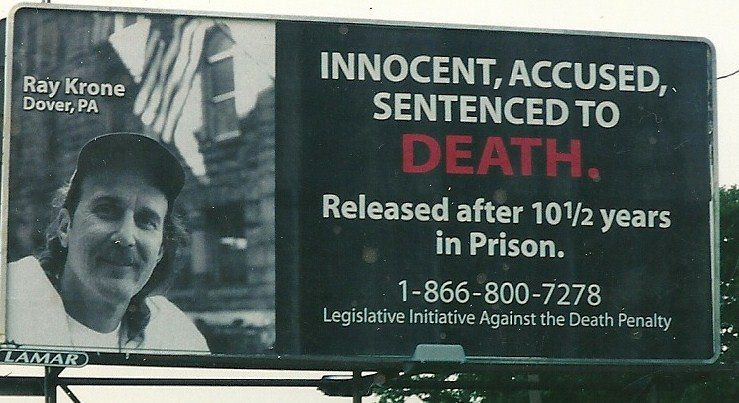

Double jeopardy – The Fifth Amendment rule states that a person cannot be made to stand trial twice for the same offense.

Badge Bunny – A woman or man who is over-the-top romantically interested in police officers and firefighters, and pursues them relentlessly. And I do mean REE-Lentlessly. They sometimes follow officers around while they’re on duty. The eat in the same restaurants. Watch officers from afar. Bring baked goods to the police department. Call in false reports that bring officers to their homes. Stand or park nearby the police department during shift changes. Make friends with dispatchers, hoping they’ll help get them closer to the officers who make their stalking hearts go pitter-patter. They drive fast, hoping an officer will stop them for speeding, an opportunity to flirt. And, well, you get the idea. REE-Lentless.

There’s an old cop saying, “The badge will get you a bunny, but the bunny will eventually get your badge.”

* Badge Bunnies have been assigned a variety of nicknames by officers, such as beat wives, holster sniffers, and lint (because they cling to uniforms).

Now, a final thought …

Here’s a easy rule of thumb to remember that’ll help to sort out the murder/homicide issue.

- All murders are homicides, but not all homicides are murder.

See, not confusing at all …

WAIT! We forgot to address the semi-automatic revolver. Is there such a thing? Well, typically the answer would be no. However …

See, I told you the only things consistent in police work and the law are the inconsistencies therein. And that’s a fact … maybe.

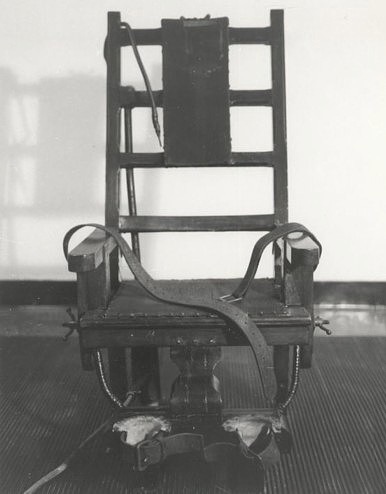

I sat twenty-feet or so from Spencer as he was put to death in Virginia’s electric chair. The procedure was gruesome, to say the least.

I sat twenty-feet or so from Spencer as he was put to death in Virginia’s electric chair. The procedure was gruesome, to say the least.